As a preamble, I have to say that Emanuel was an outstanding forum and launch pad for me as a teenager in the 1960s. London was the contemporary cultural capital of the world then and the centre of it was only a few minutes train ride from Clapham Junction station. Looking back, because the school played such a significant part in the lives of my family and friends, relating such history and anecdotes adequately could prove difficult to condense, but here goes:-

I joined Class 3C (more about my academic problems later) in September 1964, just in time to see the school rhythm & blues band, The Thyrds, reach the final of the Ready Steady Win TV contest and attend my first (and their last) gig in the Hampden Hall with my sister Jane. I’ve never forgotten their superb stage act, which was almost a Yardbirds tribute, with Paul Ellis blues-wailing on harmonica, hair flying everywhere, blasting out favourite standards such as Got My Mojo Working. What a great warm-up for what was to come three months later when I saw our joint heroes at the Hammersmith Odeon after I was lucky enough to have an old school friend, Nick Radin, offer me a spare ticket for the Beatles Christmas Show there. It’s hard to imagine the hysteria then surrounding this phenomenon, but look at the newsreels on YouTube and the Hard Day’s Night movie to get some idea of the shows by ‘the fab four’ in January 1965, and amongst the support acts was Eric Clapton with the Yardbirds: Fabulous. As a coda to this I took my son Oscar to see this reformed legendary band playing at the Pigs Nose pub in South Devon some forty years later and he is now in the business himself as a guitarist-singer. He has recently released his first 12” vinyl record as a solo artist.

1. Oscar Browne ‘If Only’ EP 2023

At Emanuel, after school hours, the famous Marquee Club in Wardour Street could be reached in time to join the queue for the evening shows, which featured the best rock acts in the world, for well under £1 a ticket. This was just before the first ‘supergroups’ were formed and big money entered the Rock game at the end of the Sixties. But it was during my first term in ‘Lower 5 General’ that I dashed down to East Putney station one afternoon, determined to finally attend the kind of gigs that senior boys had been talking about for years: it was momentous! After a couple of hours queuing, on a November night in 1966, I walked into the small hallowed arena in front of the stage to see a wall of Marshall amps and speakers ‘on Standby’, ready to deliver the glorious waves of shattering sound that had recently become possible by developments in British audio amplification factories. In the hands of masters, the blissful tones and crackling energy during performance was unsurpassed and I remember, better than yesterday, the Cream coming out on stage, plugging in and launching into their breath-taking opening number, NSU – life for me was never quite the same again, notwithstanding the ringing in the ears for a couple of days afterwards!

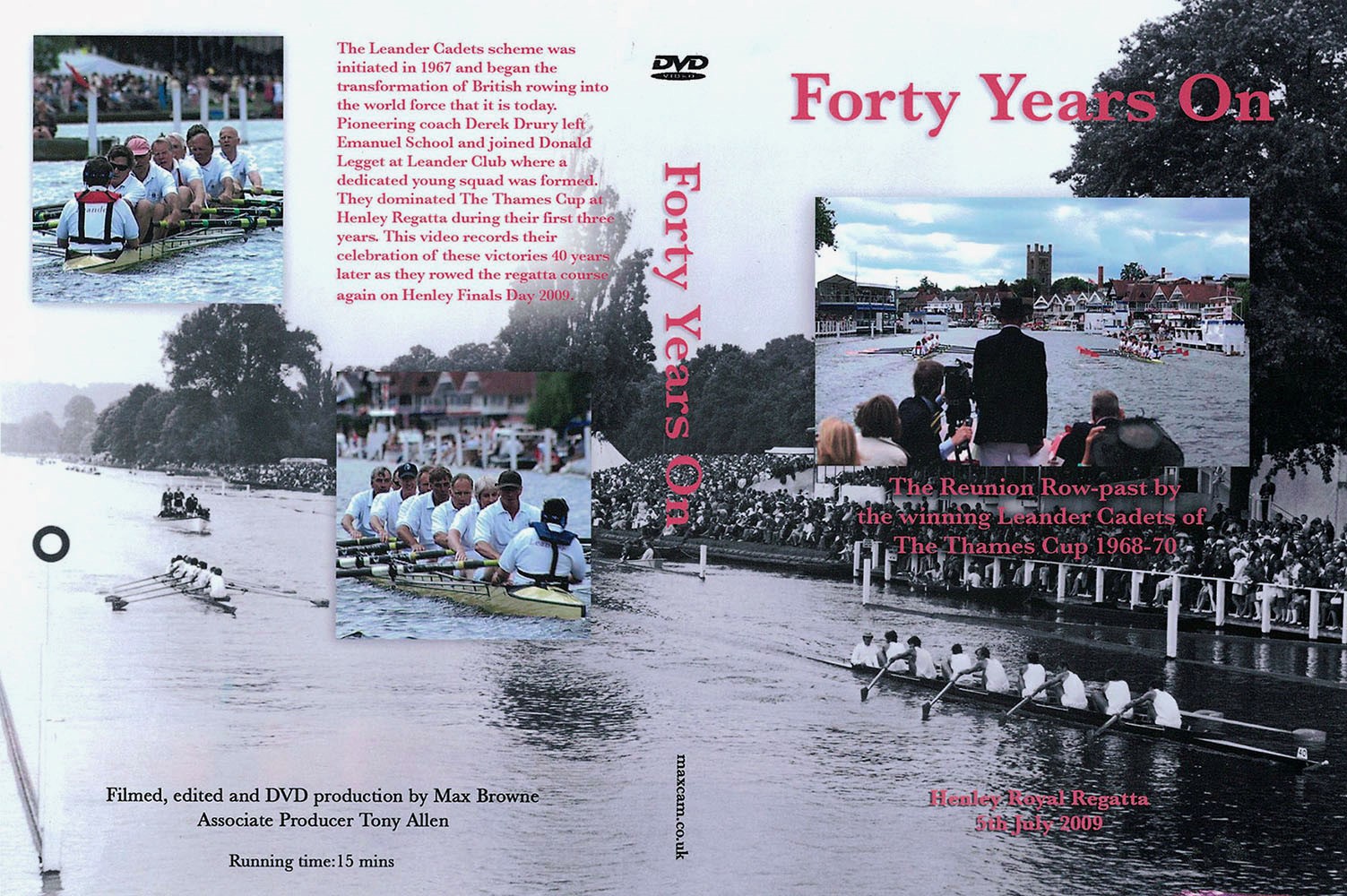

The next day, Wednesday, was principally rowing training in eights, based, as today, out on the Tideway at Barnes. This was my year in the Colts crew [2] attempting to follow the Ist 8’s stunning reputation after their win at Henley Royal Regatta a few months before. Most of these seniors were still in the top crew and their momentum under the recently departed High Priest of Emanuel rowing, Derek Drury, inspired their followers sufficiently for ESBC to rule the waves of the Thames for the rest of the decade. I didn’t acquire my first 35mm SLR camera until the following year so can only describe the sight and effect of seeing those ultra fit, strong and utterly determined guys in the club house and their training both in the gym and out on the river – Olympians in the making! A shot of the Ist Eight beating RMA Sandhurst in the 1967 Ladies Plate at Henley, by me, was published in the autumn edition of the Portcullis. Also that autumn, after leaving school, several of the crew were reunited with Derek Drury as Leander Cadets based at Henley. They were seminal as the first step in the formation of the British National Squad and its later contribution to rowing history. Forty years later I was commissioned, by my OE friend and crewmate Tony Allen, to film the Leander Cadets (with its many OEs) and Derek Drury celebrating their Thames Cup victories with an honoury row-over during Henley Regatta in 2009 [3]. I must donate a copy of the DVD to the Rowing Museum in Henley as well as to the school, to join OE Dan Kirmatzis’s excellent ESBC history tome published around the same time.

2. Emanuel Colts Summer 1967

3. Leander Cadets ’40 Years On’ DVD cover

Emanuel was widely grounded in both sporting and cultural activities and I guess it’s hard to imagine now, in our increasingly clamped down society, that senior boys were running the .22 rimfire shooting range at lunchtimes [4] and the RAF Cadets section were taking off from the sports field in their glider and trying not to land on the adjacent railway tracks too often! [5] I was a somewhat reluctant rating in the Naval section for a while [6] but did manage to shoot a perfect dual ‘100’ with Martin Rickman to win the House shooting competition for Marlborough. Several decades later I won a gold medal at Bisley for carbine shooting and firmly believe that shooting is a valuable discipline for responsible people and for its role in country pursuits and defence of the realm: something that is beginning to rear its head again! It is not widely known that the Swiss nation have no sizable army but feel reasonably safe since nearly every home includes a service rifle under the control of its trained citizens.

4. Boys against OEs shooting competition 1968

5. Glider flying 1968

6. Cadets Inspection 1968

Martin and I teamed up again, with his brother Simon, to enter and nearly win the School Music Competition in 1968. Scores were based on a ‘clapometer’ installed in the Hamden Hall, but as our band were playing a contemporary blues number (not from musical notation) we were downgraded off the top spot. A photo of me playing my one and only lead guitar appearance there, taken by Tony Allen, now serves as my ID thumbnail at the RockArchive photo agency.

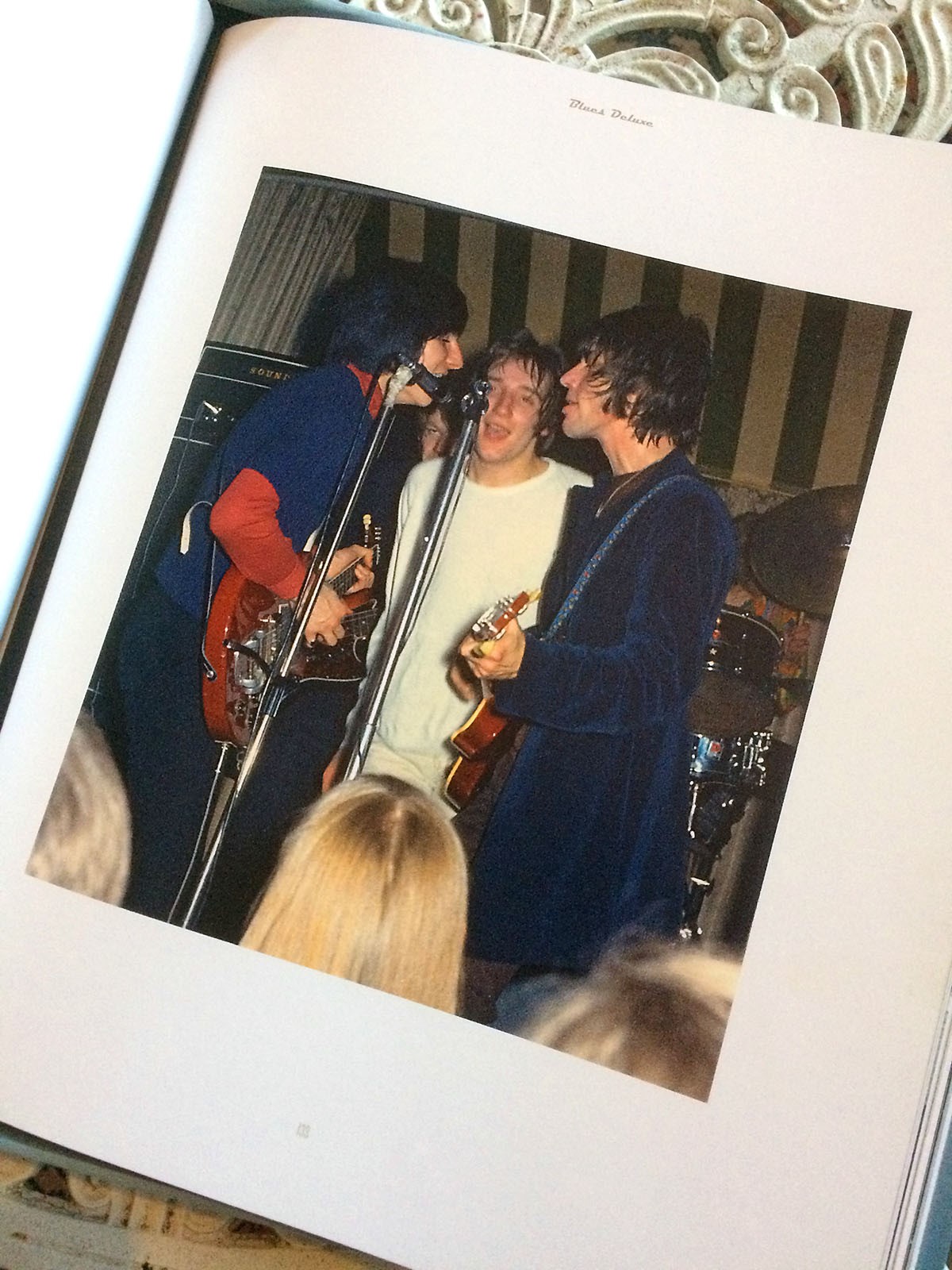

Photography had been a passion of mine before joining the school but it was only when I acquired a 35mm Pentax during my 5th Year Easter holiday that it really took off. I was so keen to get started with my new toy that I took it to the Marquee Club with a few flashbulbs (glass bulbs filled with magnesium) to see what I could get of the Jeff Beck Band debut gig there. I had the wrong kind of colour film, about 10 bulbs and was back behind several rows of standing fans. However being 6’ 2” I managed one shot that ably captured the late great Jeff, Rod Stewart and Ronnie Wood all gathered around one microphone belting out the chorus to Hi Ho Silver Lining (Jeff’s somewhat reluctant top ten hit). Crude though my kit was then, Jeff chose this shot, half a century later, as an illustration of that special moment for his lavish autobiography published by Genesis in 2017 [7]. Some months later during the summer holiday another historic event presented itself although it wasn’t realised how important it was to become at the time. Although sad again, to relate about another late great genius, Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac were playing their debut at the biggest annual musical event in the UK: The National Jazz and Blues Festival at Windsor. By then I’d got organised, with black and white film, telephoto lens and doubler (for extra magnification), electronic flash and installed a 3ft wide darkroom at home (the gap between the central heating oil tank and wall) to develop film and print the results.

7. First rockshot – Jeff Beck Band debut April 1967

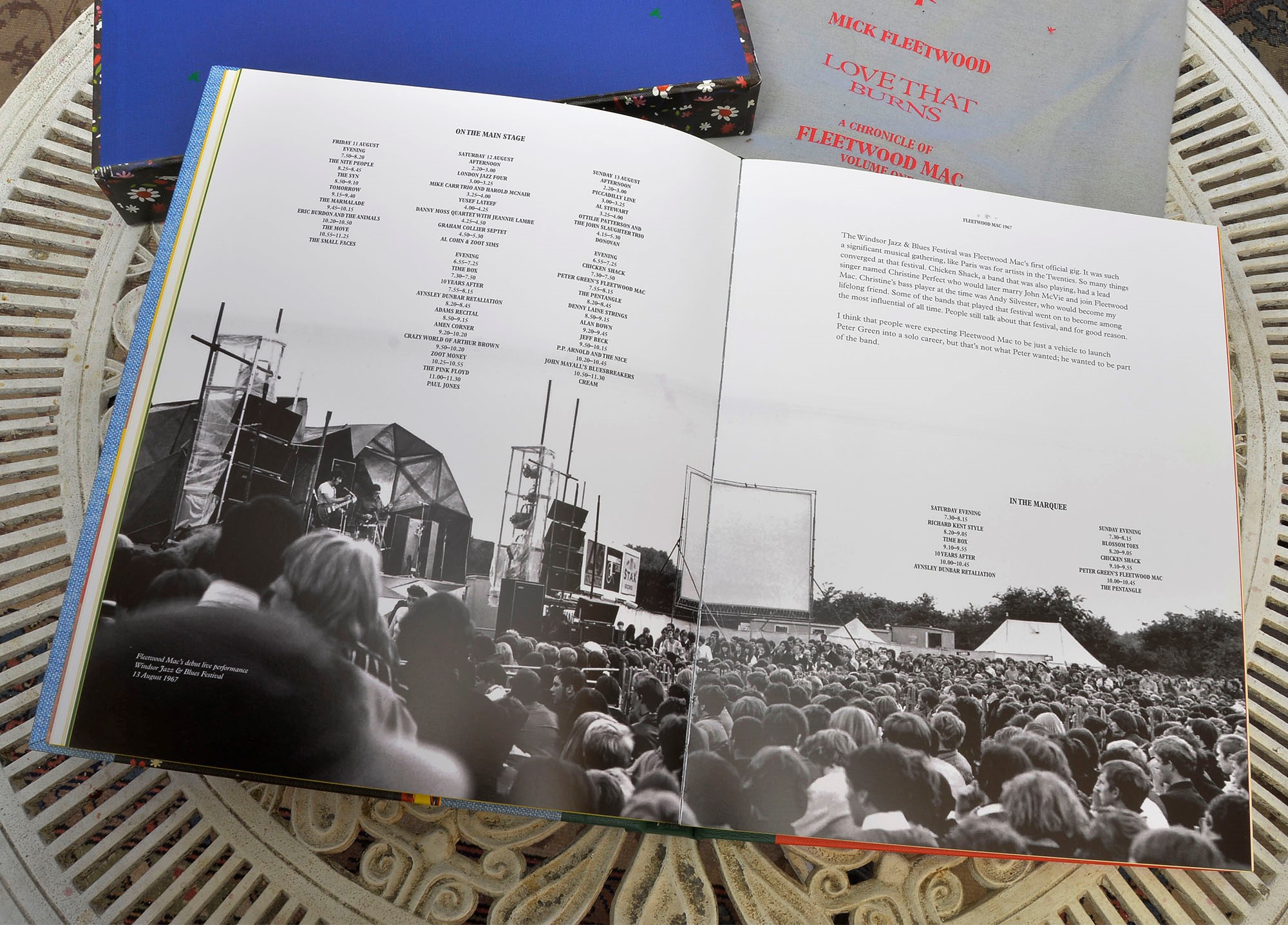

This is not the place to go into long and vivid descriptions of such events but I shall just say it accorded with the beginning of a reputation for being at the right place at the right time with the camera-shutter released at the right moment. At the Fleetwood Mac debut I was way back in the crowd but saw all the pros in the press enclosure in front of the stage and yet, so far as is known, I was the only photographer to capture this epic launch of what was to become one of Rock’s greatest bands. I’m still amazed about this and Mick Fleetwood is very pleased to have the photos, since they were again featured in his 50th anniversary biography of the band, Love That Burns, as well as most previous ones too.[8]

8. Fleetwood Mac debut August 1967

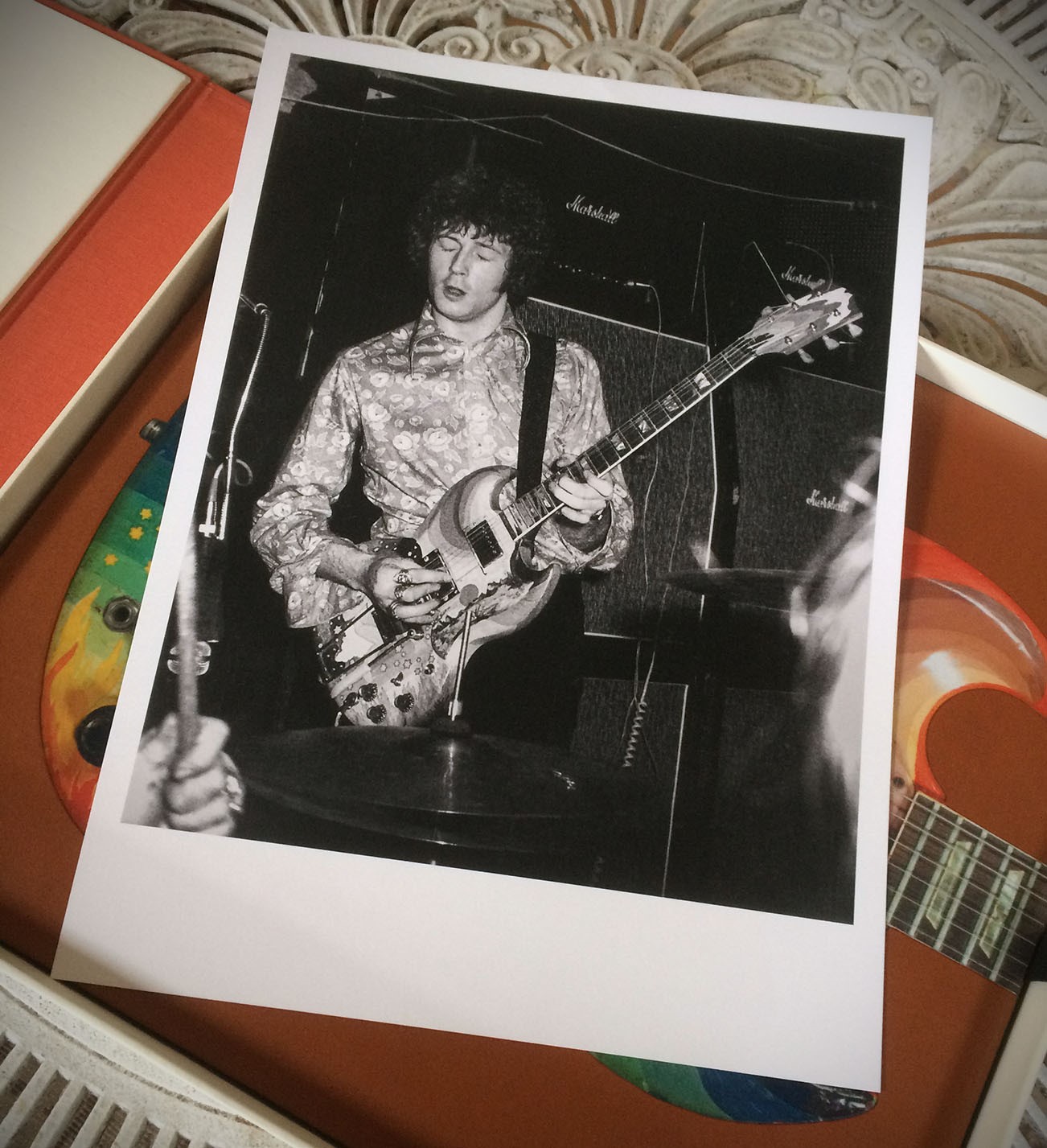

In February 1968 I was very pleased when Beat Instrumental magazine published my first rock photo: it was of Eric Clapton playing his famous psychedelic decorated guitar with Cream, who, it was reported, had just returned from a somewhat highish tour in the States! Again, fifty years later, it was used as the deluxe edition gift presented with a recent, lavishly illustrated, biography of Eric [9], which also featured dozens of my shots of him over the decades. It is gratifying to be able to embellish the career tracks of your heroes in such a way.

9. First shot of Eric Clapton in 1967 republished as an ‘expensive freebie’ in 2019

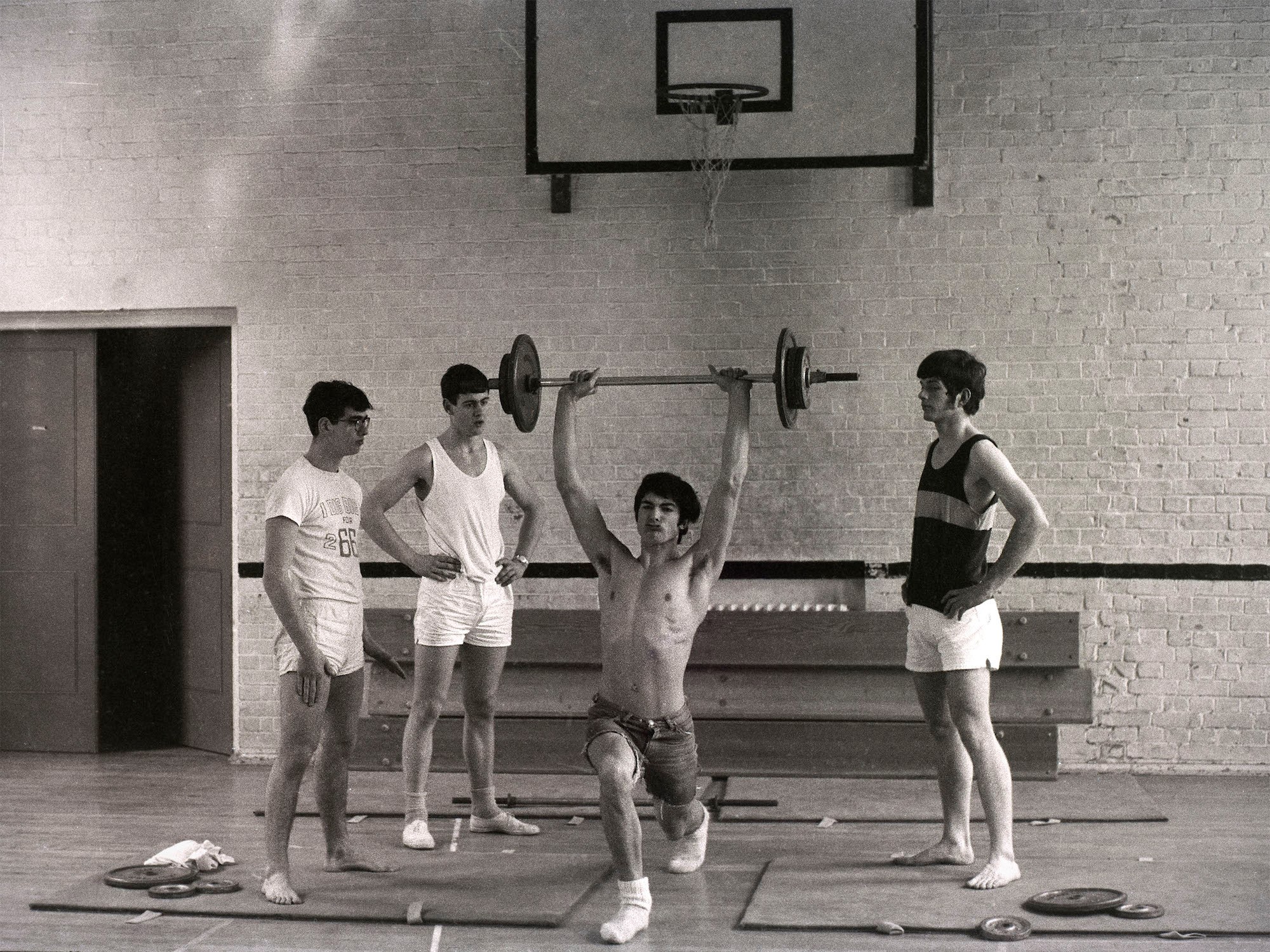

Alongside capturing pieces of rock history, I continued to photograph activities at Emanuel until leaving school, in 1969. and often provided photos for illustrations in the Portcullis as well as being commissioned to cover events such as house dinners, school plays and a rather tricky one to record a highly reflective silver cup for Rodney House. In my archive are hundreds of shots of rowing training [10] and Emanuel crews at regattas [11] and also some small nuggets of history such as the 1st 8 outing with the Oxford Boat Race crew in early 1970. This was particularly noteworthy since two exceptional rowing brothers, Nick and OE Gerry Dale, were pacing each other – in different boats![12]

10. ESBC weightlifting in the school gym, 1968

11. Evening outing at Henley 1969

12. Emanuel pacing Oxford in 1970 (with a Dale brother in each crew)

Back in school, in spite of all the successful extra-curricular activity, I remained hopeless at passing academic exams. This was mainly a result of disliking parroting information, when there were so many more interesting original things to do, and a failure to recognise that this is exactly what is required to impress examiners. My naïve concept of needing to master a subject to get good marks was only eclipsed years later, at degree level, when I learned simply to ‘give them what they want’ – a profound indictment of much human activity of course, but one that eluded me at school. This problem was obviously recognised by the Emanuel powers that be at the time as I was awarded the Whitaker Prize at the end of the 5th year. It was effectively an award for the ‘best boy in the worst class’ and gave me a great boost as I was dragged into the Sixth Form with only three O’Level passes between my legs. This was allowed by studying for A’ Levels and resit O’s at the same time (5 were required).

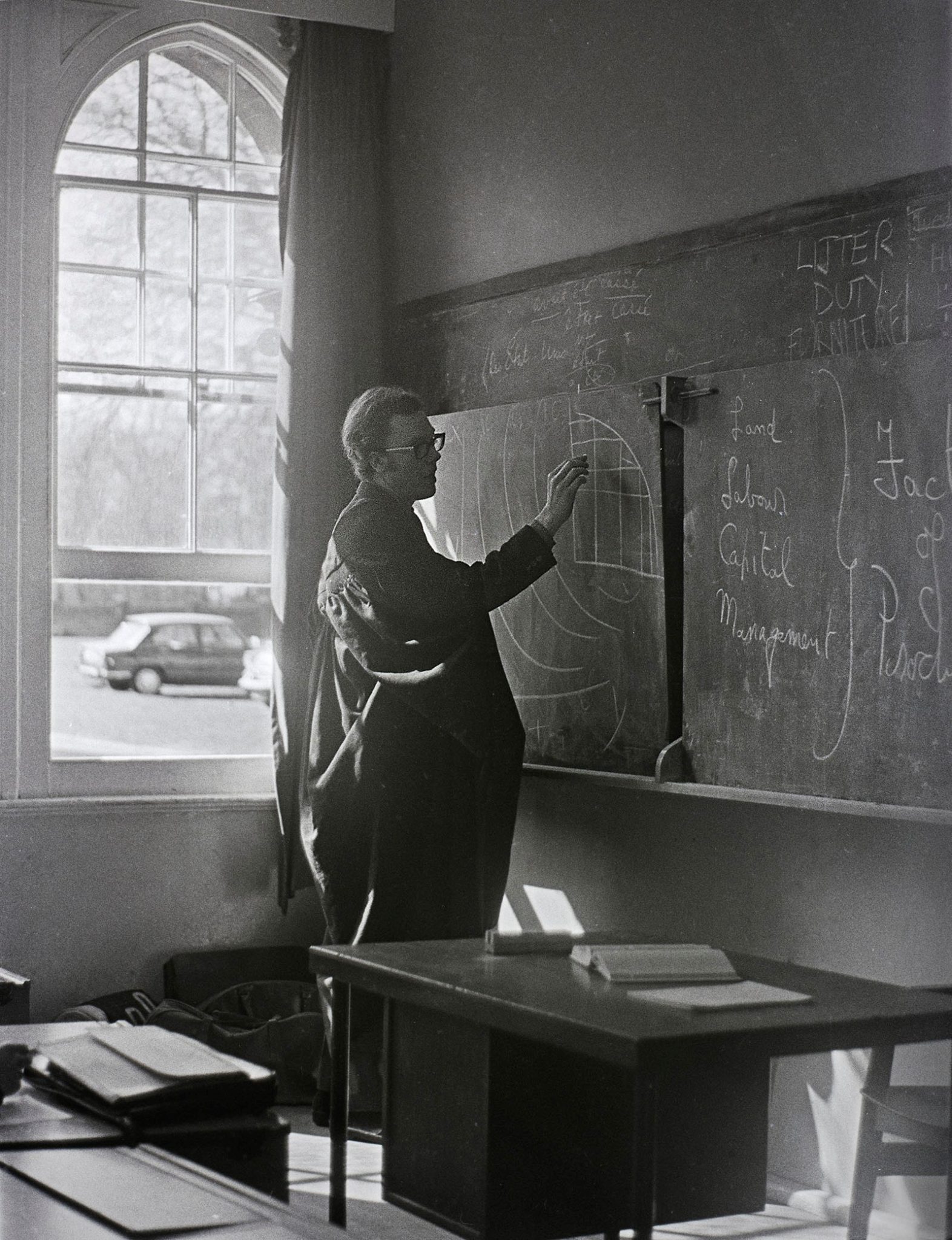

Enter the great Irish orator and economist Casey McCann [13]: How lucky were we to have this anarchic socialist master to guide us through late 1960s politics, philosophy and economics![14]. Entering his class was like those at Hogwarts –you never knew what to expect and it was always vivid and interesting.[15]

13. Casey McCann, City of London visit, 1968

14. Emanuel Economics students visiting the Barbican in 1968

15. McCann’s Economics class 1968

I became his pet challenge and was ordered to read the New Statesman and The Guardian to broaden my outlook. I did and passed A’ level Economics early, along with Dick Bradburn, fellow 1st 8 crew member, before the regatta season began in 1969. A few months later we won the Schools Head of the River race again [16] but just lost our Princess Elizabeth final at Henley to the top American seeds, Washington Lee High School. I later learned a valuable lesson about this from Alexander Walker, an international sculler I was chatting to at a celebratory ESBC dinner in 2010: in physical terms, he explained, it is possible to exceed your ‘elastic limit’ in athletic performance and I now believe that this is what happened to me towards the end of what the official Henley Regatta Records race-report describes as ‘a grim struggle’ against the Nautical College, Pangbourne in our semi-final race the day before [17]: it was rowed in the hottest part of the day, with no hats – probably some dehydration. I could only crawl out of the boat with my vision reduced to monochrome.[18] It was the closest I’ve ever felt to dying and it took considerably longer than normal for the crew to get the boat out of the water and probably some months for me to fully recover. This explains the shock of Washington Lee taking us off the start the following day in the Final. It had never happened before: we were always faster off the start than other schools and we spent the rest of the course catching up – we didn’t quite. Our grateful opponents told us afterwards that they thought we would! That is sport and if we hadn’t suffered such a gruelling semi, I believe, as we all did, that ESBC would have won the PE for the second time. C’est la vie!

16. Going afloat for the Head of the River race 1969

17. Official Henley 1969 PE semi-final photo

18. The memorable way back after the 1969 PE semi-final

In contrast to a supreme effort that fails is one that succeeds with almost no stress at all. It is worth relating an example of this, going beyond being even ‘in the zone’, such that an individual’s performance goes way beyond all expectations. Such a phenomenon took hold of me on the day of the ESBC Regatta, at Barnes in July 1968. Prior to this, the crew had returned to school after their fortnight stay at Henley had unfortunately resulted in a PE Quarter Final defeat and several weeks of summer term remained with few classes. So sculling up the Thames to Richmond and back on sunny days was a very pleasant wind-down option. It was rare to be rowing in such a non-competitive way and felt quite holiday-like in mood. The school regatta took place just before term ended and, as far as I remember, the races were organised as knockout heats. I’d always been an average sculler at best and had no expectation of winning. However I was one of the strongest and fittest in the club and somehow, as a result of my extra curricular practise, all came good on the day and I sculled the best I ever have, by a large margin, to win the event. It was easy and I was hardly out of breath and have to admit I was as surprised as everyone else. You see this kind of thing featured on-screen sometimes but it sure is fab when it happens to you and you can say ‘it was my day’.

As indicated earlier, like all great schools, Emanuel has its share of outstanding teachers who inspire their pupils sometimes to a life-long degree. But this educational inspiration later bought up a serious quandary for me when I became a successful Economics graduate (with a BA Hons 2(1): After years of academic struggle getting there, I then attempted to follow it with a business career path that ended up leading me nowhere – I was a round peg in a square hole! Just because you understand demand and supply curves in Economics and light and sound waves in Physics doesn’t mean you should follow career paths in those disciplines.

The problem can best be seen in the light of the fact that I was enjoying selling rock star photos to the international music press before I left Emanuel, as I was good at capturing performance with a camera. However that was fun and I didn’t foresee that I could make an adequate living pursuing such activity as a career – but how wrong can you be?

My father Barry founded the ESBC SUPPORTERS in 1968 along with Arthur Bradburn and Harry Todd. This was a very effective initiative in funding much needed new boats and maintaining a high level of interest in rowing achievement at the school. He also motivated me to get a degree and so ‘join the club’, something he wasn’t able to do as a result of his wartime service. At that time students were paid to enter higher education, with fees paid and grants to live on, and so it was a directive that was hard to refuse especially if you could gain a place on a degree course in London, as I eventually did at Middlesex Poly. This was a 4 year ‘sandwich course’ with the third year out on placement. The college in Enfield had easy access to all the major London venues and galleries and so music and photography carried on for me intermittently during the sophisticated, inspirational and somewhat bohemian student life in the early 1970s ‘Prog Rock’ era.

Although late in applying through the college, I managed to get the only 3rd Year job placement I wanted – with Samuelson Film Service Ltd. (European Panavision agents). This was the film equipment company with whom my OE friend Dick Bradburn’s late dad had been Head of Sound. He had been interested in me entering the sound department there before leaving Emanuel but I’d passed on it, as I had at a place at Ealing School of Photography, paved for me by fellow photographer school-friend Ramon Szmichowski. Anyway now, in 1973, I threw a temporary career dice at ‘Sammies’ and won straightaway. It turned out to be a fabulous year and I was almost oblivious to the stresses of political and industrial problems such as national strikes and the ‘three-day week’. Perhaps this was also due to a rekindled romance with a flame first met as a result of ESBC crew partying years before.[19] Incidentally such partying also resulted in my sister Jane meeting and later marrying fellow Ist 8 crewmember Andy Todd and she also wishes to remind readers of the rousing ESBC chant, that she and friends often joined in with on riverbanks, which so contributed to the bonhomie and success at regattas: this was “DING OI, DING OI, DING OI, DING A LING A LING, OI, OI, OI, EMANUEL!” So, resonating with this, life was good, although the future was somewhat blurry.

19. Celebrating the end of 20 years of formal education, St. Tropez, 1975

My first love had enlightened me that I was ‘a romantic’ just as I left Emanuel. However I certainly don’t attach any blame to the school for this affliction and, to its credit, the career guidance was to follow a technical path rather than an academic one: so Emanuel is in the clear on that one! But once a good degree was achieved it seemed silly to ignore it and turn to what seemed a self-indulgent life in the media, particularly when you’re in love and thinking of providing for a future family and such responsibilities. Of course there was also an element of fear of failure and the ‘I told you so’ syndrome! Thus began my ‘career in the Doldrums’ era.

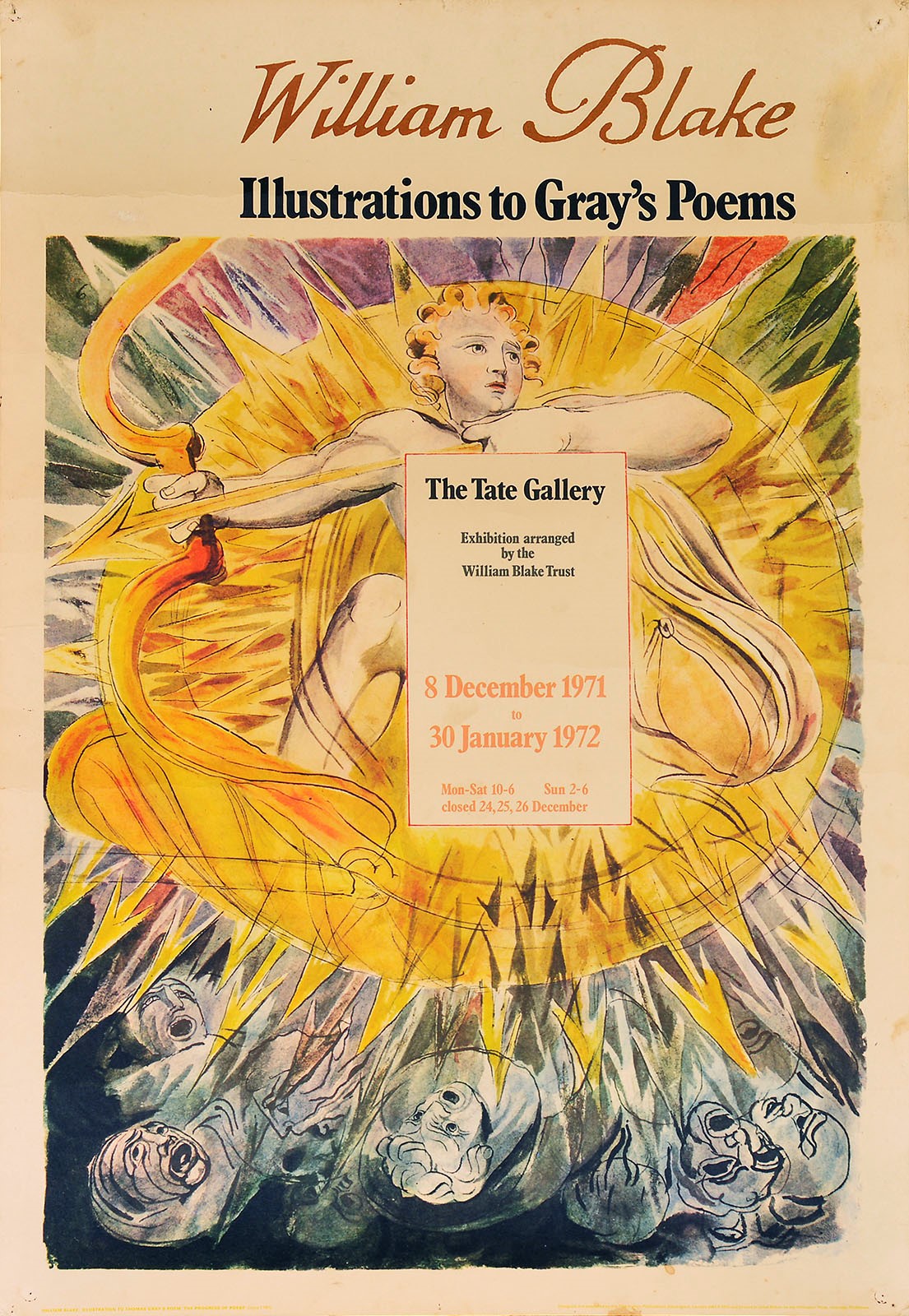

Before this, in my first year at college, the romantic (aesthetic escapist from reality) in me emerged strongly in the form of a quest to discover how artists had depicted heaven and hell through history with the associated torments and triumphs. This was slightly belated, for which I can blame the syllabi at Emanuel, since it didn’t allow both Art and Music courses to be taken together. I chose Music at school and as I endeavoured to catch up with Art at college, I dived into this fascinating arena in the well-stocked library there and one unique and celebrated figure stood out – William Blake.[20] I devoured his designs, spirituality, anarchism and poems and was able to access rare facsimile volumes of his prophetic books through inter-library loans. Thus started my life-long odyssey with Romantic Art history, a successful one, I believe, largely as a result of being an insider: As I am one, ‘a Romantic’ that is, things tend to fall into place, follow familiar paths and passions flair with understandable causes and results for most participants and this includes me too, as I now realise, after unravelling both the public and private sagas of many others.

20. Tate Gallery William Blake exhibition poster 1971

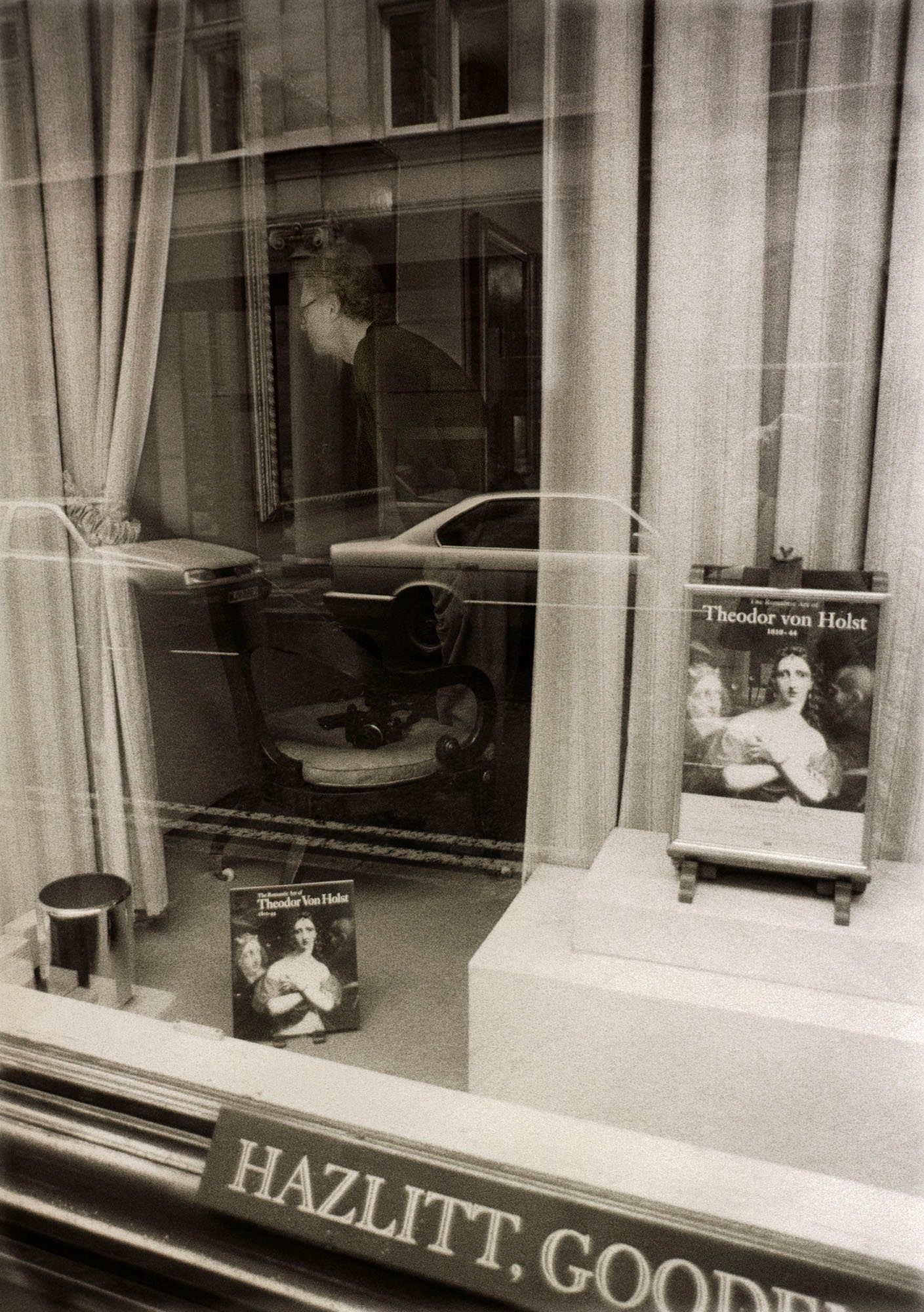

The principle form this took for me was in the research and rescue of undeservedly obscure Romantic artists from oblivion (to paraphrase Gabriel Rossetti). Blake and his friend Henry Fuseli’s 19th Century followers included a fascinating young London artist, Theodor von Holst, the first illustrator of Frankenstein, who tragically died in London in 1844, aged only 33. In 1976 what little could be seen of his art inspired me, in the midst of my career doldrums, to unearth more. I did and discovered a painting, owned by leading art critic to be, Brian Sewell, was the key to Rossetti’s claim of Holst as an artistic link to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, of which he was the leader. Holst’s 1841 painting of The Wish [21] depicted a mysterious fortune-teller that became the inspirational source for Rossetti’s first published poem in 1852. The significance of this discovery was sufficient for a short article to be published in the world’s top art history journal, the Burlington Magazine. Not a bad start for an academic school dummy! It did also prove a remark made by one of my college lecturers: that completing a degree course would enable you to research and write about anything. In many circles it is also the ticket to further a career and be taken seriously – although not for a craftsman.

21. Theodor von Holst ‘The Wish’ 1841

Over the decades that followed, interest in the emerging art of the followers of Fuseli, the extraordinary Keeper of the Royal Academy, amongst others, led me to contribute articles, catalogues and curate and review exhibitions worldwide on this variously dark side of British Art. I am also proud of a unique ‘honoury post-grad degree’ that Brian Sewell awarded me in his London Evening Standard review of the first Theodor von Holst exhibition in 1994.[22] However all this passionate activity, although a pleasant and enlightening sideline, never paid the mortgage. I thus had to follow my talents in a more pecuniary direction to put food on the table.

22. Brian Sewell assessing the first Holst exhibition, 1994

After launching my art history career, losing my girlfriend and getting nowhere in mail-order advertising, I accepted an invitation to take off across the pond for a break. Arriving in New York in September 1978, I met my art history mentor Professor Gert Schiff, who we have to thank for all the initial research on Gustav Holst’s great-uncle Theodor and the superb 1975 Tate Gallery exhibition on Fuseli. I visited him at his residence, the famous Chelsea Hotel, just before Sid Vicious murdered his girlfriend there. He was happy for me to take the reins on Fuseli’s closest followers and was very generous in support of his self-taught protégé!

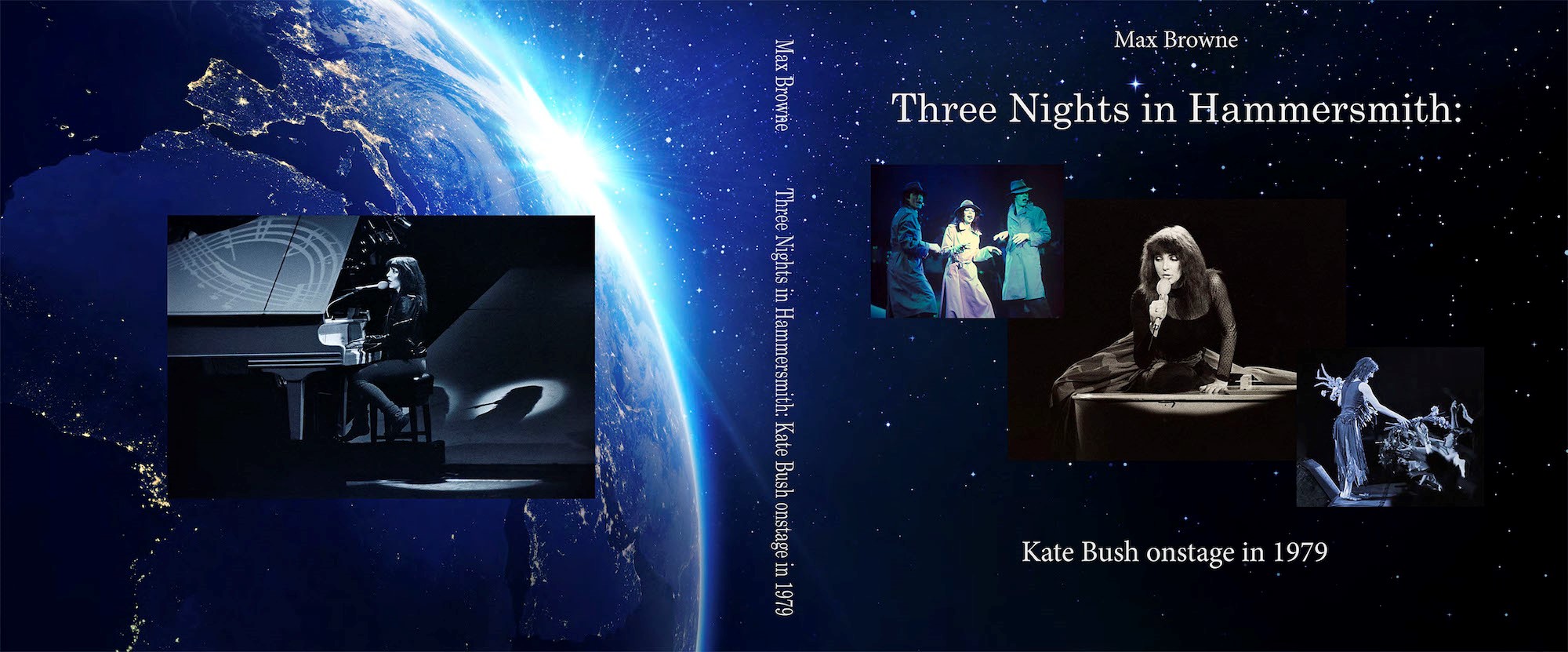

Following an enjoyable and enlightening stay amongst the NY skyscrapers I ventured South: a 1300 mile Greyhound Bus trip to Miami and a two hour plane journey bought me to Grand Bahama island where I stayed with a friend who was working at a dive shop where I soon obtained my PADDI diving qualification (so much better than the stodgy British Sub Aqua Club that I had given up on at college). A friend of hers ran a tax free photo shop and before leaving the island I bought two superb Nikon lenses in a sale which, a few months later, proved perfect for low-light stage photography. Back in London the punk era was in full flow and I joined in when I could shooting gigs by The Clash, Elvis Costello and Blondie. My best, favourite and, for me, seminal stills coverage was published recently, as a ‘lockdown special’ book of illustrations: Three Nights in Hammersmith [23] presents a photographic montage, in song order, of the last three nights of Kate Bush’s one and only tour. Seeing and shooting these magical unmatched shows was something like a divine experience. Nothing like it in rock had ever been seen before and Kate was at her stage performing peak. I was sorely in need of some kind of career inspiration and here it was – a photographic dream where fairy-tales came to life. The second of the nights clinched it for me: a television outside broadcast crew had been commissioned to record the two hour show and the cameramen alongside me were being paid for their heavenly coverage – I had to become one of them. It took a while but, having at last decided what to do, I started – ten years after leaving Emanuel.

23. Kate Bush book jacket 2021

Thus real work started for me in 1979: firstly six months as an audio-visual assistant and then back to Samuelsons, the film equipment company that I had been placed with as a student five years before. They wondered what had happened to me in the interim and welcomed me back. However all was not completely rosy in the sense that the Managing Director still saw me as management material whereas I saw myself as a cameraman. At the time the film and TV industry was a trades union ‘closed shop’ and access to work was only through possession of a union ticket, which was usually obtained after many years of training and waiting for vacancy opportunities. ‘Sammies’ was a union shop and, unusually, the top management were also members as most had been cameramen. I soon became a member and was able to take advantage of the huge advances in equipment technology at the time. There was a shortage of technicians for ‘video playback’, the means by which film camera shots could be replayed back for Directors to watch on monitors to assess their ‘takes’ during production. After training I was often sent out to work on commercials for TV and cinema release at studios such as Pinewood and Shepperton in this role and learned a lot about large scale filming from the best technicians in the business: a truly fabulous education that occasionally included being on set for movies too. For anyone with camera aspirations, watching features and commercials being lit, rehearsed and shot cannot be beaten as apprenticeship education. Such technical artistry cannot be learned adequately at college and neither can ‘hunting’ with a camera in the documentary arena. This is an entirely different discipline that requires maximising the real life prospects offered, selecting them and then capturing them to a pattern of pictorial narration, that ‘gives them what they want’ in a different way to storyboard production. Generally documentary footage cannot be tightly scripted as is larger scale production, apart from Television Outside Broadcast coverage, which is another arena. Thus documentary cameramen have to approach their shooting from a reality narrative point of view, as well as photographic, in capturing interviews, establishing shots and shooting ‘B roll’ cutaways (extra filler shots) in order for editors, in turn, to ‘give them what they want’. For a stills photographer particularly, this is a steep learning curve and one that, more generally, never really stops.

From being on the huge Pinewood set of Superman 2 [24,25], when I started, to covering international medical conferences in Regents Park, when I finished, has been a varied and fascinating camera career – and as they often say in camera departments, ‘it beats working for a living’! For youngsters of my ilk, I would proffer some advice: Follow your interests and aptitudes and don’t be deflected otherwise you will always be competing with others more interested and better than you. Enjoy doing whatever you’re good at and the chances are that you’ll . . . ‘give them what they want’ and maybe more!

24. Superman 2 set – Pinewood 1980

25. Villains ‘superpuff’ down NY Broadway – Pinewood 1980

Finally reverting to other pursuits and my stills sideline again, I have to thank Tony Allen for opening the wonderful arena of transatlantic and Caribbean yachting to me over many years, once he had completed his training and become a charter yacht skipper, based in English Harbour, Antigua.[26] He and his wife to be, Sarah, hosted many trips for me to shoot the Classics and Race Week regattas there and they also featured in some of this coverage for Boat International and Classic Yacht magazines [27]. I must get down to editing all the shots of our yacht delivery from Brighton to Antigua in 1987. This voyage started in the aftermath of the hurricane that brought down roofs and trees all along the south coast and Tony spent the night fending off his new 60 foot sloop Korsar II from the harbour wall – with his feet! In contrast the warm and pleasant tropical trade winds that later blew us across the pond was like balm, including 24hrs becalmed in the middle of the Atlantic![28] Ever since the first European explorers sailed to the Caribbean Islands, reaching them by sea has had the same effect, that of achieving a heavenly goal.[29]

26. Tony & Sarah sailing Vixen in the Virgin Islands 1986

27. Boat International Antigua regattas spread September 1991

28. Becalmed mid-Atlantic on Korsar II 1987

29. Probably the best Happy Hour venue on the Planet – Shirley Heights, Antigua

Going forward I have plenty of art and photo projects to keep me busy and it’s nice to know that The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art would like to relieve me of my art history archive once it’s ready to donate. I hope that some of my Emanuel material will follow a similar path too, back between the railway lines.

Originally planned as a short memoir, I can only apologise to any readers still remaining for what actually appears to be the start of an autobiography. Time to cut this short if the editor hasn’t already! However I would like the last words here to acknowledge the role of OE John Meeus (1942-51), friend and mentor to my father, who was instrumental in my attending Emanuel: Thank you John.[30, that’s also him, far left, in the rifle-range image – no.4]

By Max Browne

30. John Meeus & Max in the library in April 2019, after half a century

Further information on the areas of interest mentioned above can be found at my fledgling websites:-

http://www.ednaclarkehall.org.uk

By Max Browne (OE1964-69)