War memorials across the country and beyond play a significant role in the annual act of remembrance, which this year falls on Sunday 10 November. The Emanuel School First and Second World War Memorials name approximately two hundred and fifty soldiers who lost their lives out of the overall one thousand seven hundred who served in both wars. An occasional new name is still added as a result of ongoing research or via family enquiries. Having two hundred and fifty names read aloud, which occurred on the Friday 8 November chapel service, takes a considerable length of time and is both a sobering and moving experience putting into perspective the true level of loss.

During my time at the school, we have carried out extensive research into the war experiences of our alumni. This lead to the book Emanuel School at War written by Daniel Kirmatzis and myself, published exactly a decade ago. When our pupils visit the First World War battlefields of the Somme, we feature the ‘Emanuel experience’ by seeking out OE graves, names on memorials, and reading trench letter extracts written by our alumni. Also, when I lead historical tours of the school for London Open House, Wandsworth Historical Fortnight, or alumni events, we often have a moment of reflection in the chapel, highlighting some of the tragic stories and losses connected to the alumni listed on the memorials.

During the First World War, as the era of Emanuel School boarding ended, the chapel continued to hold services on a Sunday evening, and it was here that many boys first heard of the death of their former schoolmates and friends. These names were eventually added to the War Memorial, however, there were several mistakes. These make fascinating stories, some of which are detailed in the remainder of this remembrance article, focusing on the First World War memorial inaccuracies.

Imagine reading your own obituary! Several Emanuel boys did just this as letters and news poured in from all fronts in the First World War. The editors of the termly school magazine The Portcullis were dealing with large volume of correspondence and news of a serious wound could easily be misconstrued as ‘killed in action’ if no further news were forthcoming. It might end with an obituary in the Old Emanuel Notes and, unless corrected, eventually the War Memorial.

In the case of Lawrence Inkster the Trinity Term 1918 Portcullis noted, “The deaths are also announced of Lawrence Inkster, who will be remembered by older Emanuels for his scholastic successes.” Fortunately, this error was amended quickly, as in the Christmas issue a correction was swiftly published, “It is now my duty to offer apologies and congratulations to Capt. Lawrence Inkster, who has had the unusual privilege of reading the announcement of his own death in The Portcullis. Capt. Inkster writes to tell us that he is alive and well. ‘I was wounded on September 20th, 1917 and am at present with my reserve battalion at Sittingbourne.’” Lawrence’s sons later also attended Emanuel, with Donald serving in the Second World War.

Lawrence Inkster and wife

In the Summer Term 1917 Portcullis the following announcement was made: “Can anyone give us news of S. W. Lund, of the RAMC? He went out to Serbia with the Medical Mission in the early days, and we have received no news of him once.”

On this occasion the old saying of “no news is good news” was clearly ignored as if you look closely at the First World War memorial in the chapel today, you will see the name of S. W. Lund has been scrubbed out. We will never know exactly how his death was ‘confirmed’, but the reason he was scrubbed out becomes obvious when reading the Summer Term Portcullis in 1943; we are told:

“An OE named Lund has written in mild protest to say that he is included in the War Memorial in the chapel!” It took almost thirty years for this mistake to be noticed and then amended!

Inkster and Lund were not the only individuals who were ‘brought back to life’; Alwyn Kerfoot Hughes received the same treatment. Alwyn’s son Nicholas, who also attended Emanuel in the fifties, never realised that the ‘A. Hughes’ on the memorial was his very much still alive father. After joining up Alwyn was sent to France and was wounded on the Somme and taken prisoner. After about three months in a German hospital, he was sent to a POW camp at Minden where he remained for the rest of war. Perhaps too much was read into his silence, or there was another rumour which was accepted for fact.

Apology note from school historian

In 2013 the grandson of Richard Clifford Montford contacted us to donate a 1901 edition of Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield which his grandfather had been awarded as a prize in July 1902. The Lent Term 1918 Portcullis noted “Mander tells of hearing the death of Montford in the Machine Gun Corps.” This was another unverified death with Richard also being added to the memorial based on second hand information. Richard was the fourth of eleven children and had two daughters born in 1914 and 1916. After the war he lived in Wimbledon, working in sales, dying in 1966, fifty years after his first ‘death’.

R C Montford

R C Montford and family

These alumni are joined by three more: Entwistle, Hammett and Brooks, the last of whom had perhaps the most memorable ‘resurrection’.

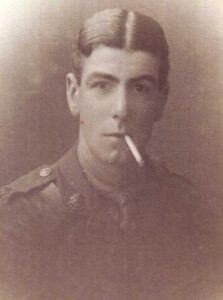

Percy Mathison Brooks attended Emanuel between 1907-12 and was a keen rugby player, competing for the Second Fifteen. In the Christmas Term Portcullis, this update is provided:

“P. M. Brooks, Sec-Lieut. in the North Staffordshire Regt., who has also been killed, displayed in the Army the dogged characteristics for which he is remembered at Emanuel. He was a member of the Second Fifteen, and boxed for the School against Wilson’s, winning what was practically a punching match by sheer endurance.”

Percy M Brooks in uniform

Few details are known about Percy’s war service after being appointed temporary 2nd Lt. in 1917. We know he served with the BEF in France, Flanders, and Salonika and at some point, during this time was wounded. He attended an Old Emanuel gathering in the summer of 1916 but a year later was presumed to have been killed. The reason for this remains a mystery.

Portrait of Percy M Brooks

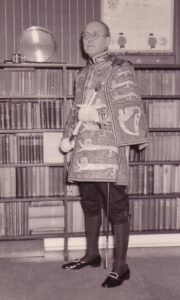

Very much alive, after the war Percy returned to England and in the 1920s lived on Bedford Road, Clapham. In the early 1930s he was Editor of the Melody Maker, a popular and long running weekly British music magazine. During his editorship he interviewed two of the biggest names in twentieth century jazz history, Duke Ellington, and Louis Armstrong.

If chatting with Duke Ellington was not enough of a claim to fame, then perhaps being the individual responsible for shortening Louis Armstrong’s nickname comes close to ensuring Percy has an interesting footnote in jazz history. In July 1932 Percy greeted Louis Armstrong when he arrived with his band at Plymouth. At this time Armstrong was known by the nickname ‘Satchelmouth’ but as the musician told interviewers years later, when Percy greeted him, he and his band members heard Percy say, ‘Hello Satchmo.’ The exact nature of how Percy came to call Armstrong ‘Satchmo’ is unclear, but because the story originated with Louis Armstrong himself it has added validity, even though some refute it. In several interviews in the 1950s and 1960s Armstrong claimed that one of his band members thought Percy had called him ‘Satchmo’ because he thought Armstrong had more ‘mouth.’

Percy M Brooks with Duke Ellington

Percy served with the RAF on barrage balloon duties in the Second World War. These great silver-coloured balloons half-filled with hydrogen were stationed across London with the aim of deflecting the German bombers. Percy, who led a most interesting life, died in 1945 shortly before the war ended.

Correct death of Percy M Brooks – Noted in Melody Maker 1945

The school historian Charles W. Scott-Giles OBE (OE1902-11) and his Old Emanuel Association colleagues from the First World War era deserve great credit for the incredible work they did in bringing together Emanuel School’s extensive Pro Patria and Roll of Honour. Lt. Col Charles Hill was largely responsible for the Second World War memorial lists.

First World War Memorial

Second World War Memorial

When Dan and I were researching our book Emanuel School at War we had considerably more resources at our disposal and were impressed by the thoroughness and detail of the research which preceded us. Scott-Giles served in the Army Service Corps and lost many friends in the war; later he wrote several editions of Emanuel’s most authoritative school history. In 1916 his song ‘Pour Bien Desirer’, itself a war poem of sorts, was sung for the first time, becoming the ‘School Song’ for many decades. Many alumni from the fifties eras or earlier knew the song off by heart.

Wilfrid Scott-Giles

There is a unique and very personal story behind each of the 250 plus OEs remembered on the two Emanuel School War Memorials, even the small number who did not actually die in the conflict but were amongst the brave 1700 who served. Remembrance Day shines a light on every name.

First World War Memorial in the 1920s

Tony Jones (Emanuel School Archivist) and Dan Kirmatzis (Historian, OE1994-2001)