Since January 1883, countless children have sang, worshiped, listened to stirring services and concerts in the school chapel. Next year the main building, known as the Saxon Snell building, after the architect who designed it in 1872 originally as an orphanage, will celebrate its 150 anniversary. However, many of the fixtures and fittings are significantly older and were originally housed in the Emanuel Hospital chapel in Westminster. When the school relocated in 1883 it was felt that taking as much of ‘the heart’ of the chapel would ensure memories of the old hospital would live on.

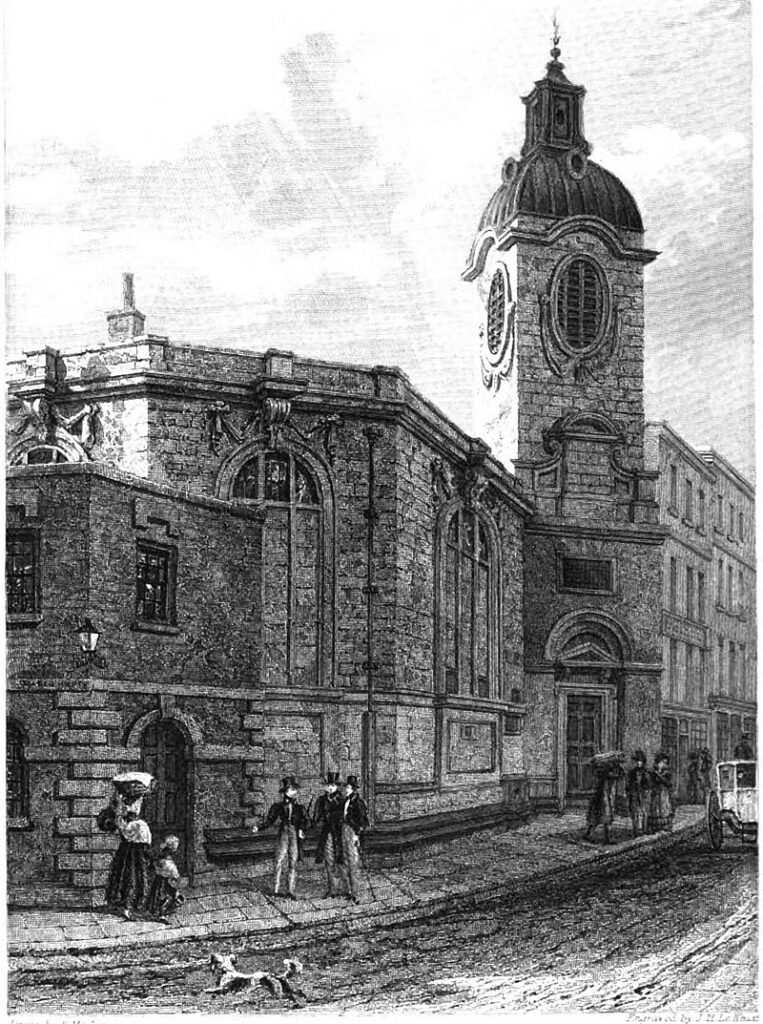

Most of the more ornate furniture came from Westminster, including the altar-table, the eagle lectern and the pulpit. Interestingly, all of these objects in the sanctuary had only been in the possession of Emanuel Hospital for 37 years by the time it relocated in 1883. All were purchased from the Church of St. Benet Fink in the Cheapside area of London, which was demolished in 1845. This was a very famous London church, which had been designed by Sir Christopher Wren and was often called ‘The Wren Church’. We will never know which famous preachers and religious figures spread the Christian message from this very special eagle lectern down the years.

The earliest Emanuel School histories also note that the lectern was rescued by an art loving Alderman from a Flemish shrine at the time of the French Revolution. There is undoubtedly a fascinating, but hidden, history, associated with this striking lectern.

Emanuel’s connection with the famous St. Benet Fink Church does not end with the eagle, as the 17th Century portraits of Aaron and Moses which hang in the school’s chapel, also originated from St. Benet Fink, being bought by the Emanuel School Governors significantly earlier, in 1673, at the price of £12. These two paintings dominate the back wall of the school chapel and have their own convoluted history.

Every official school publication states that they were painted by an “anonymous artist” in the period 1610-30. In 2011, a Sotherby art historian, Ben Hall (OE1981-86), returned to school to give them a professional once-over, noting that they were very much in the style of Anthony Van Dyck and Peter Paul Rubens, (superior) foreign artists, who were heavily copied during the period of Charles I.

Ben expands:

“The works of these foreign born artists had a profound effect on the native artists of England. We can see their influence on the unknown painter of the panels that hang in the Emanuel Chapel. They are stylistically very similar to works by Rubens. Such grand panels were almost certainly commissioned by a church or chapel to decorate the walls with Old Testament figures. The paintings may very well have been part of a larger series of such paintings that have been split up over the years. Although there is no certainty as to who the artist is, he was possibly a painter that was commissioned to create such works for religious institutions in the city of London.”

While one can speculate as to the circumstances under which the artist painted; nothing at present is known regarding the works’ early provenance. What truly makes these two paintings remarkable is that very few of this type and date exist in London. This is because, while Charles I encouraged the renaissance of English art, in the 1650s, Cromwell and his men destroyed a great deal of religious paintings.

However, when we were researching this article, new information came to light:

There is nothing in the official school histories to contradict Ben’s assumptions, however some years after his research we uncovered an earlier article by Paul Hetherington “The Altarpiece for Wren’s Church of St Benet Fink” which credits the paintings to artist Robert Streeter (also spelt Streater), of which very few religious pieces have survived, he also painted landscapes and portraits.

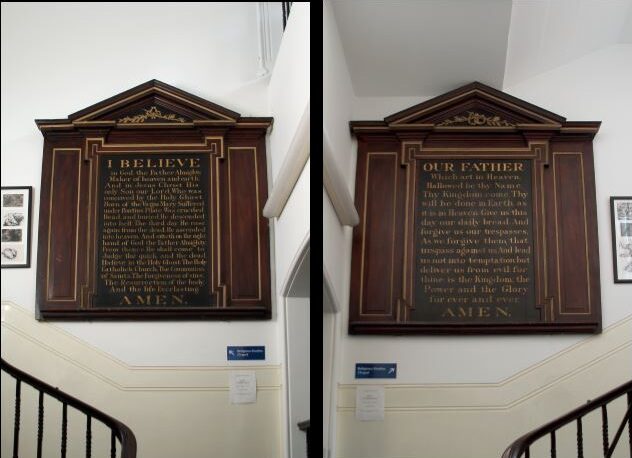

Hetherington states that this artist was known as “Serjeant Paynter to Charles II” and that his major surviving work is in the Sheldonian Theatre (Oxford) and a few other churches, including St Michael’s Cornhill (also Aaron and Moses), which the researcher says is incredibly similar in style to our paintings. Hetherington supposes (the article was written in 1995) that few academic art scholars or Wren experts, will have ever seen the Emanuel school paintings, or are aware of their existence and it can be argued that they are amongst the very best large-scale examples of his surviving work. Particularly as the five panel St. Benet Fink set has remained intact, the other three being the Commandments, the Creed and the Lord’s Prayer. Two of these are currently directly outside the chapel and the third above the inside door, either side of Aaron and Moses.

One might wonder how Paul Hetherington came across these paintings at all? This mystery was solved by his son Andrew Hetherington (OE1982-89) who told us that that his dad “was introduced to the paintings when he came to hear me sing in the chapel. It was seeing the paintings that took him on that particular hunt [which led to the article], rather than the hunt taking him to Emanuel.”

It is often difficult to verify the authenticity of artwork, particularly those which are so old, and whether they are by Robert Streeter or not, they remain outstanding examples of British religious art in the 1600s, particularly as the set has been kept together.

Tony Jones (Emanuel School Archivist)