For many years, the late Henry Carpenter (OE1939-46) ran the Canadian branch of the Old Emanuel Association (OEA), connecting members who found themselves in his country and regularly sending news of reunions to the OEA Newsletter. In 1975 Henry wrote to the magazine seeking help in tracing Euchi Matsuyama (OE1927-32) whom he believed to be in Canada. Henry was almost certainly chasing a very old lead, as Euchi (actually spelt ‘Eiichi’) had been in Canada in the 1940s but had returned to the UK during the Second World War.

One doubts Henry ever located Matsuyama as he was seeking a needle in a haystack. In 1947 Eiichi changed his name by deed poll to Eric Maxwell to distance himself from Japan and the negative connotations caused by the war.

Our Archivist, Tony Jones, has pieced together Eiichi’s fascinating story with help from his family and reference material.

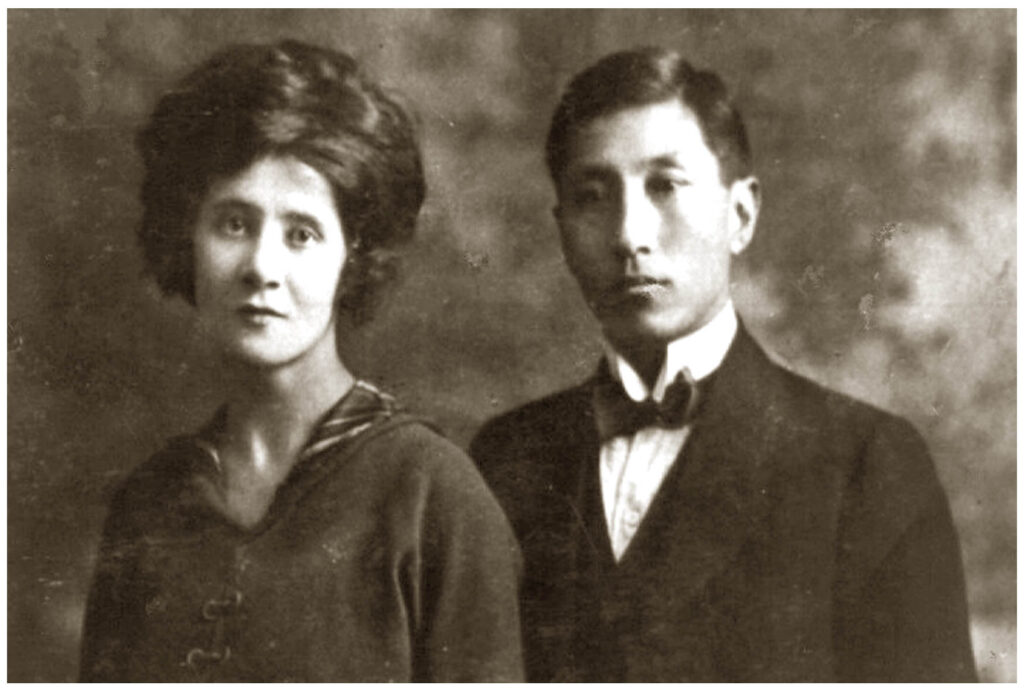

In the early decades of the 20th century there were relatively few non-British pupils at Emanuel School. Eiichi’s father, Ryuson Chuso Matsuyama, arrived in the UK in 1911. He was an artist who also did antique restorations and watercolours on both paper and silk.

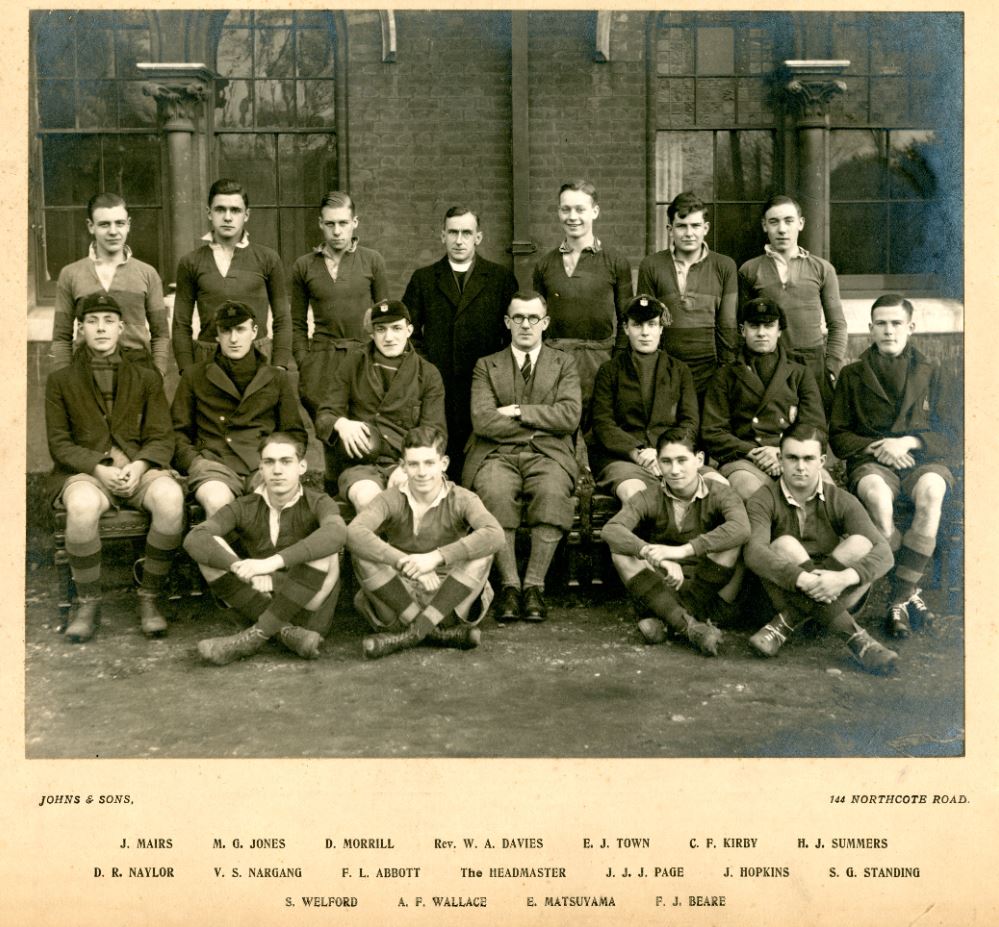

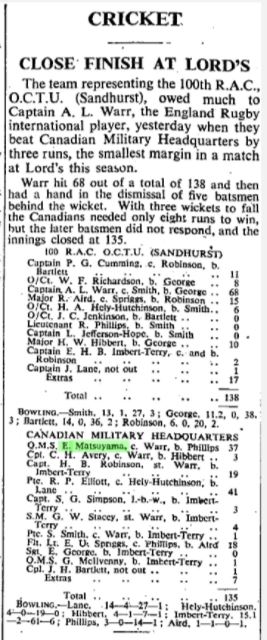

Eiichi travelled to school from Norbury and was an exceptional athlete who represented Clyde House and eventually played for both the First Rugby XV and Cricket XI. As a bowler he had great statistics, regularly taking multiple wickets for ten runs or less. A great athlete and sportsman, he competed in many senior events whilst still a junior. In later years he represented the Canadian Military Headquarters cricket team and played at Lords. Eiichi also sang in the Chorus of the Musical Society and won a language prize for French in the Speech Day of 1929.

After leaving school, Eiichi remained local and played for the Old Emanuel 2nd XV where “he combined excellently at half-back”. Between 1936 and the period leading up to the war Eiichi wrote a series of letters to the Old Emanuel Association which were partially published in The Portcullis.

Eiichi moved to Japan in 1935 and became known as the OEA Far Eastern Correspondent. He worked as a clerk at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. At this point he spoke limited Japanese, apart from what he picked up from his father, but as he was staying with Japanese relatives, over the next few years, he became fluent.

Here are some extracts from Eiichi’s letters to The Portcullis:

1936:

“E. Matsuyama finds himself strangely enough in Tokyo and is having to learn Japanese. When he has mastered this he will be able to have jujitsu lessons, which he hopes will come in handy when he returns to England and Rugby Football! His present address resembles nothing so much as a closely veiled insult, and he himself says that “I guess that if you use a large envelope it will all fit in.”

1937:

“Tokyo is as modern as London or New York, and yet it still manages to protect that quaint Eastern charm hidden away in the side streets. One of these Eastern charms certainly seems to discourage the earnest student of Japanese culture. I speak of the frightful stench which assails one’s nostrils on the side roads.

This evil is to be remedied by the Olympic Games in 1940. Clothes are frightfully dear, as all the decent material is imported from England.

Sports are considered only to be fit for schoolboys and undergraduates. They have few clubs for chappies who have finished schooling. Rugger is played by the varsities, but if you talk of cricket to a Japanese he nods his head vaguely and seems to connect it with croquet for some unknown reason. Night life in Tokyo is frightfully dull. You see, as we are the capital of Japan and the Emperor is living here, we are expected to set a standard for the other cities to follow. All the places of entertainment are shut by midnight.”

1938:

“At night squadrons of mosquitos carry out various fancy formation attacks, so life becomes unbearable. I sleep in Japanese style on the “tatami” and I usually manage to roll off the “futon” (kind of soft mattress) and bring the mosquito net and all its trappings down with a crash. I now know what a poor fish feels like when it gets entangled in a fishing net. You struggle to get out or find an opening, swearing the while at the inventor of mosquito nets, until you finally decide it’s better to sleep as you are until morning and daylight arrives, and then you can see what a perfect fool you look.”

In around 1938, Eiichi changed job, leaving the Guaranty Trust Company to take up a post with the Mercantile Bank of India. By 1941 it was not safe for foreigners in Japan and he sailed from Yokohama on April 17th (on the Hikawa Maru, apparently the last ship to leave the country). Arriving in Seattle 28th April, Eiichi was unable to get back to England so enlisted in the Canadian Army. He appears on The Second World War Pro Patria, listed as a Sergeant in the Canadian Army, 1943-45, and became proficient in Morse Code. As Eiichi had a British mother and passport, he would have avoided the internment problems faced by many American and Canadian Japanese.

During and after the war there was a major shortage of Westerners who spoke Japanese and other Oriental languages. Considering it took around two years to pick up the basics, there was a demand for those who had even the most rudimentary skills in Japanese to pass it on. Locating appropriate teachers was complex and Eiichi became one of the very first to be recruited, none of which were first-language Japanese speakers.

By this stage he had been promoted to Sergeant Major and is listed on the Emanuel Pro Patria as being in the Canadian Army until he transferred to the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London to teach courses covering the war from July 1942 to late 1945. An article in the Illustrated London News dating from 1945 notes that part of his job in the Intelligence Corps was to practice spoken Japanese every day to help prepare future administrators by teaching them the language skills to get by in Japan.

In 1947 he changed his name by deed poll to Eric Maxwell and did not continue with his language work beyond the war. Instead, he worked as an import/export clerk for Gee Lawson Chemicals where he stayed until retirement. Euchi Matsuyama, later Eric Maxwell, led a fascinating life and whereas those who had support roles at Bletchley Park have been recognised and rightly celebrated, those who had a gift for languages are another group of Britain’s least likely war heroes which are also worth remembering.

Tony Jones (Archivist)