The Battle of Britain was fought over British skies during the summer and autumn of 1940, with this article remembering five Old Emanuel pilots who helped defend Britain during the period when most of Europe had surrendered to Hitler. The main German objective, after the successful occupation of France, was to destroy the RAF and gain air superiority over the UK, leading to potential invasion. Its failure was seen as one of the first major turning points of the war and Germany realised there would be no easy victory over Britain and certainly no surrender.

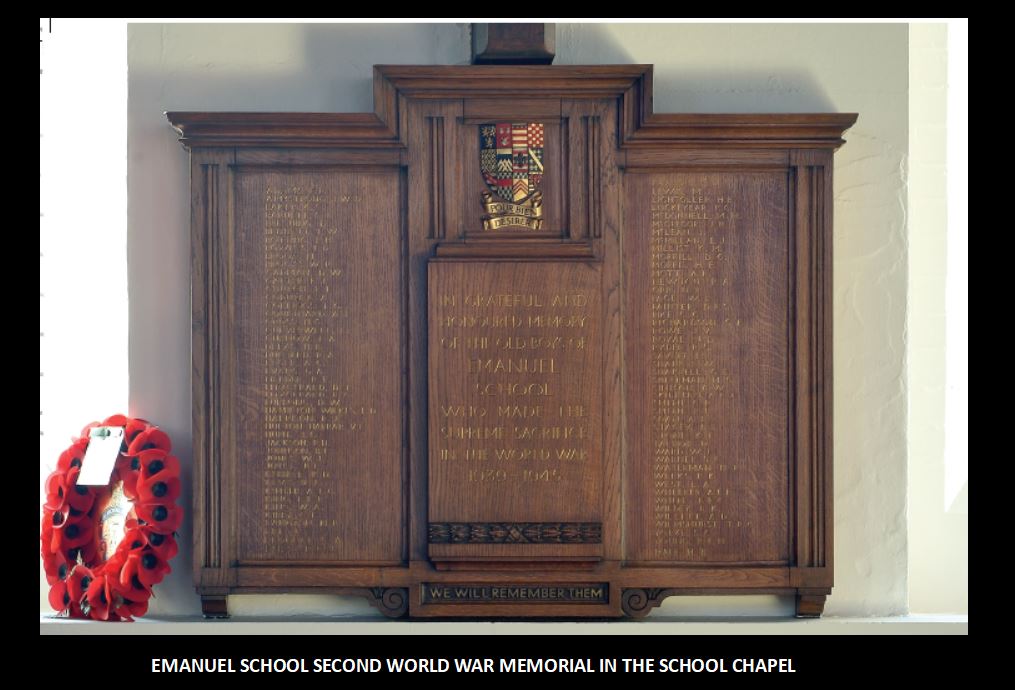

By the summer of 1940, there was no shortage of pilots willing to defend British shores. As many as 9000 signed up, of which 2946 took part in at least one action in the Battle of Britain. Around 537 pilots were killed, with total deaths rising to 1497 when other aircrew were factored into the losses. This was an exceptionally dangerous campaign against a very experienced Luftwaffe, and at least six Old Emanuels (five pilots) defended the skies, with two paying the ultimate sacrifice either in this battle or later on in the conflict.

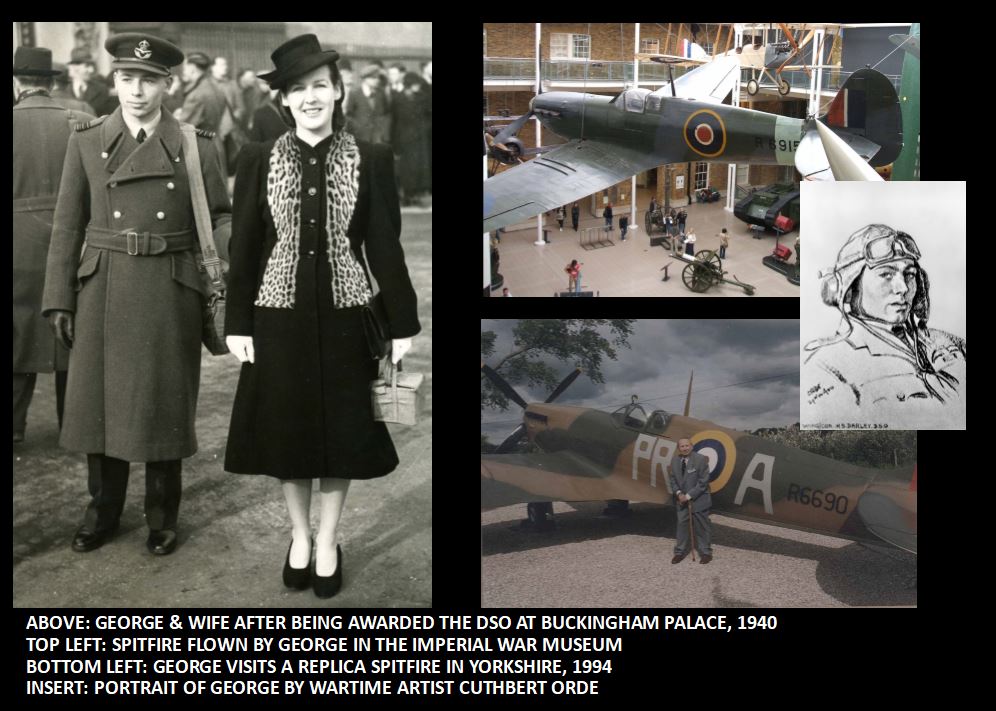

Horace ‘George’ Darley (OE1925-32) was an ‘Ace’, a term bestowed upon pilots who had more than five confirmed kills. The spitfire that George flew with the 609 Squadron for most of the Battle of Britain has hung from the ceiling of the Imperial War Museum for many years. Darley was an Emanuel School sporting all-rounder, as well as being Captain of Boats he also represented the school at rugby, fives, swimming and shooting. The shooting was to come in handy as George was a tremendous pilot and is mentioned in books detailing the battle and the clever flying tactics he used. Historian, James Holland, noted how Darley modified tactics for his squadron “he began drumming into them the importance of working as a team, of each pilot constantly looking out for enemy aircraft above, behind and below.“

Darley explains in his own words what he observed and how he came to make the vital change in tactics which subsequently reduced the number of pilots being killed:

“On return to the UK in June 1940 I was posted to a spitfire squadron in Essex. After 3 sorties I had discovered how NOT to command a fighter squadron, and on 28th June was pleased to be given Command of 609 spitfire squadron. This squadron suffered casualties in Dunkirk, and I closely questioned the pilots on how the losses were incurred. To me it was apparent that the main causes were too rigid a formation and no knowledge of deflection shooting. With my flying instructor background, I considered these and other causes as yet another flying problem which eventually led me to examine all aspects of a fighter sortie from take-off to landing. The squadron was then moved in July where I was to put my unproven theories into practice.”

In the resulting following months he led more than 80 successful missions, with the loss of only 7 pilots.

Darley was later awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his contribution to the Battle of Britain and subsequently fought throughout the war, also remaining in the RAF after its conclusion. Colin Francis (OE1932-39) was no so fortunate, and was killed in the summer of 1940 on a brutal day in which forty German craft were shot down, balanced against twenty-four British. The law of the RAF jungle often dictated that rookie pilots flew the oldest, slowest or most damaged planes with statistics showing that there were higher mortality rates amongst novice pilots flying in their first five missions. Ultimately, there was no such thing as beginners luck in aerial combat.

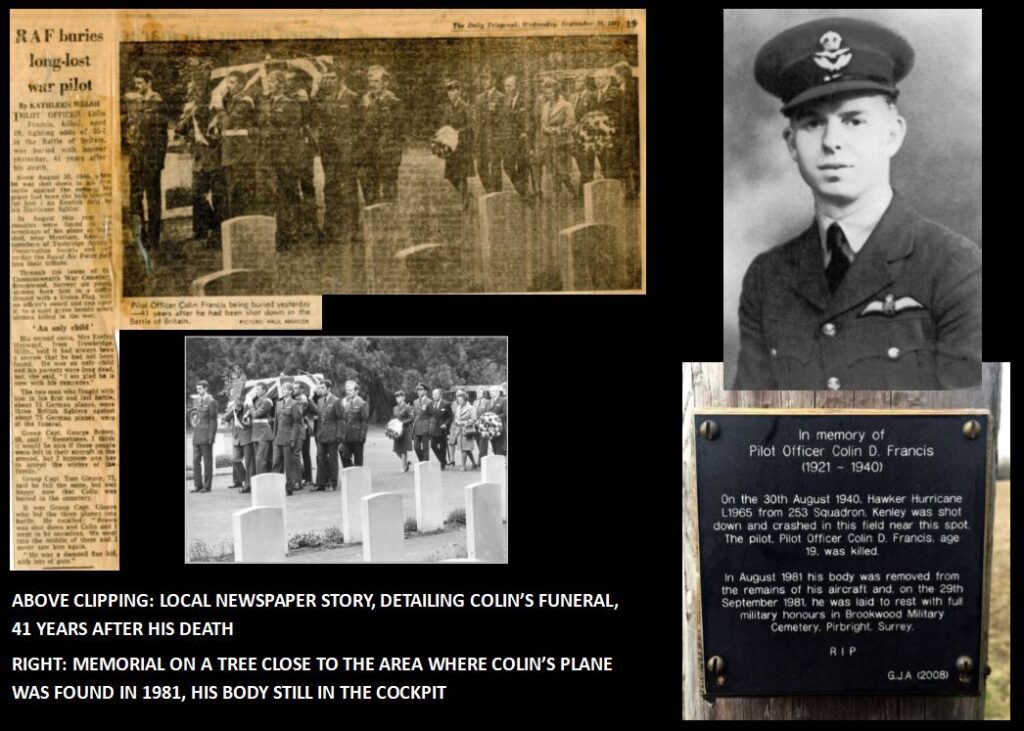

Tragically, Colin Francis died on his maiden voyage of August 30th, being killed under exceptionally brave circumstances. He had set off on a sortie with two other fighters to attack a much larger force of bombers and fighters. Fellow pilot, Tom Gleave, who was in one of the other two planes, said: “after Brown was shot down, Colin and I went in by ourselves. We went right into the middle of them and I never saw him again. He was a damned fine kid and full of guts.”

After being shot down, his plane was not recovered for an incredible 41 years. In 1941, Colin’s body was found, still strapped in his cockpit, when an excavation in a Kent farm uncovered his hurricane. He was later buried with full military honours at Brookwood Military Cemetery, and the story was widely reported in the press at the time as ‘The Lost Boy’ as he was only nineteen at the time of his death. Pilot Officer Carthew recalled after Colin’s body was recovered “we were close friends and were known on the Squadron as Tweedledee and Tweedledum”. These days the term ‘hero’ is bounced around far too easily and frequently, actors, rich sports stars and spoilt musicians are quite undeserving of this moniker, however, Colin Francis most certainly was worthy of it.

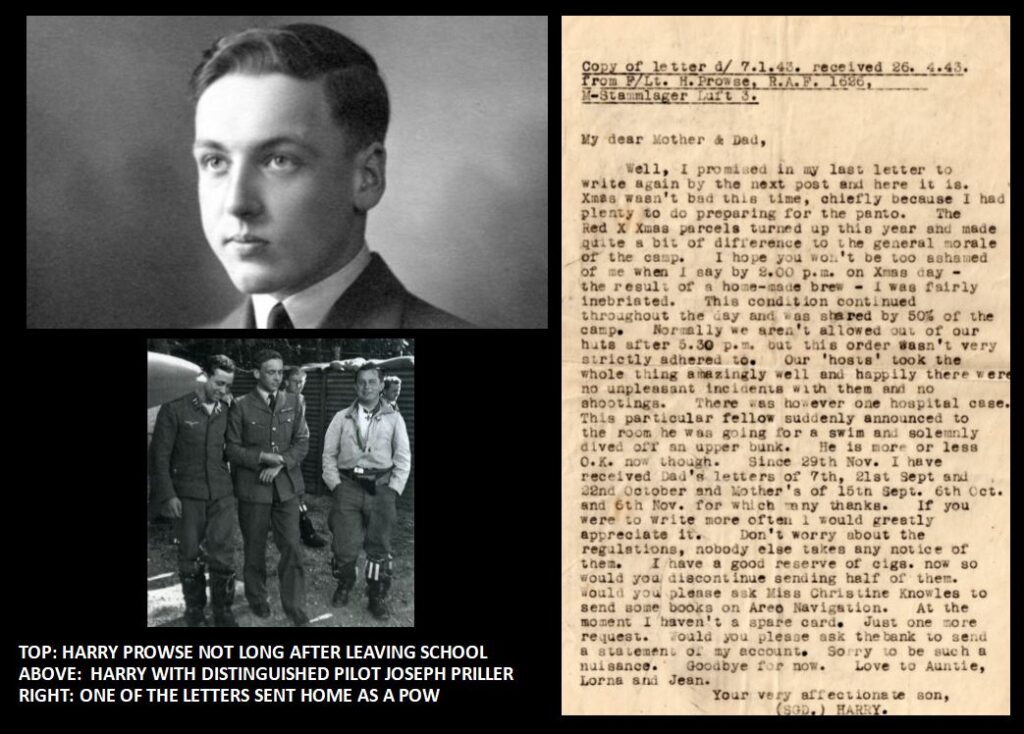

Harry Prowse (OE1932-39) also joined the RAF straight after school, where he was a Scholar, a musician and an actor, his final performance being in ‘Saint Joan’ in the winter of 1938. When Harry passed away (age 89) the obituary in The Guardian noted “As a handsome Spitfire pilot, he rarely had to buy his own drinks. But at the age of nineteen, he was fighting in the Battle of Britain, and by the time he was twenty he had been shot down twice, interrogated by the Gestapo and shipped off to the notorious Stalag Luft III PoW camp”.

After being shot down for the first time in northern France, Harry escaped back to England. However, after shooting down two Messerschmitt Bf-109s he was recaptured and spent the rest of the war in captivity. Like many of his generation, Harry found it difficult to talk about his wartime experiences, however, it was later revealed that he was “involved in the ill-fated wooden horse escape that led to the slaughter of runaway prisoners” (a part-inspiration for the famous film The Great Escape, of which Harry acted as a consultant). After surviving ‘The Long March’ through Poland in January 1945 he arrived back in the UK around the time of VE Day. He rejoined the RAF after the war, however, found it difficult to settle in the UK and opted to start a new life in Brazil where he grew oranges until his death in 2010. At his funeral, in his honour, the Brazilian Air Force staged a fly-past.

Bryan Noble (OE1927-33) was both a rower, and like many future service men, a member of the Officer Training Corp (OTC). After being shot down in the Battle of Britain (after an incredible seventy sorties) he was burned so badly he requiring surgery for his wounds. In doing so he became a medical ‘guinea pig’, with a group of other RAF pilots who had been similarly scarred in crash landings and required facial reconstruction. Upon discovery, after his crash, it took some time to identify Bryan due to the severity of his burns and damage to his vocal chords. His recovery was, in effect, the early stages of plastic surgery through skin grafting. By the time the war ended Bryan has piloted fifteen different types of planes and had been Mentioned in Despatches. Bryan rejoined the RAF in 1946 in the Flight Control Branch reaching the rank of Wing Commander and retired in 1969.

Kenneth Millist (OE1931-35) also had a distinguished school career. He was both a top rugby player and rower and was part of a very strong rowing squad in the mid-1930s era, recording good wins at Staines, Twickenham, Reading, Richmond and Kingston Regattas. Kenneth joined the RAF in 1939 and flew in Squadrons 73 and 615 in the Battle of Britain, before seeing further active service in Libya and the Middle East, where he was killed. In February 1941, he was shot down over Benina and evaded capture for three days by trekking 60km in the desert before being found by friendly Australian forces.

After returning to his unit, another crash followed before he was later killed in mysterious circumstances. Kenneth was twenty-two years old at the time of his death and is remembered on the Alamein Memorial. He was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) medal, with his commanding officer provided further details on the award: “Attacking an enemy aircraft and driving it off, then landing after the raid without exterior aids. PO Millist displayed exceptional courage, initiative and devotion to duty throughout the whole of the raid and showed complete disregard for his own safety.”

Sir William Sholto Douglas did not fly in the Battle of Britain and by that stage of his career had reached the rank of Air Chief Marshall. Sholto Douglas attended Emanuel before the First World War and was a veteran of the dangerous dogfights which took place above the trenches, becoming a founder memory of the RAF after the RFC was renamed, winning both the Military Cross and the Distinguished Flying Cross. A career soldier, in between the wars he became a RAF instructor and was Deputy Chief of the Air Staff by the time the war had started. Too old for combat, Sir William had a tactical role in the Battle of Britain, supporting an aggressive strategy to win the conflict and is remembered for his clashes with the Head of Fighter Command Hugh Dowding. From 1941 onwards he had a number of senior posts including periods in Egypt and Coastal Command during the invasion of Normandy in 1944. He was knighted in 1948.

Those who fought in the Battle of Britain are rightly remembered as ‘The Few’ as within the overall context of the Second World War those involved were miniscule, but on the other hand played an enormous role in shaping the early stages of the war. These men had nerves of steel and Emanuel School should be exceptionally proud that five of its alumni are listed amongst ‘The Few’.

Tony Jones (Emanuel School Archivist)