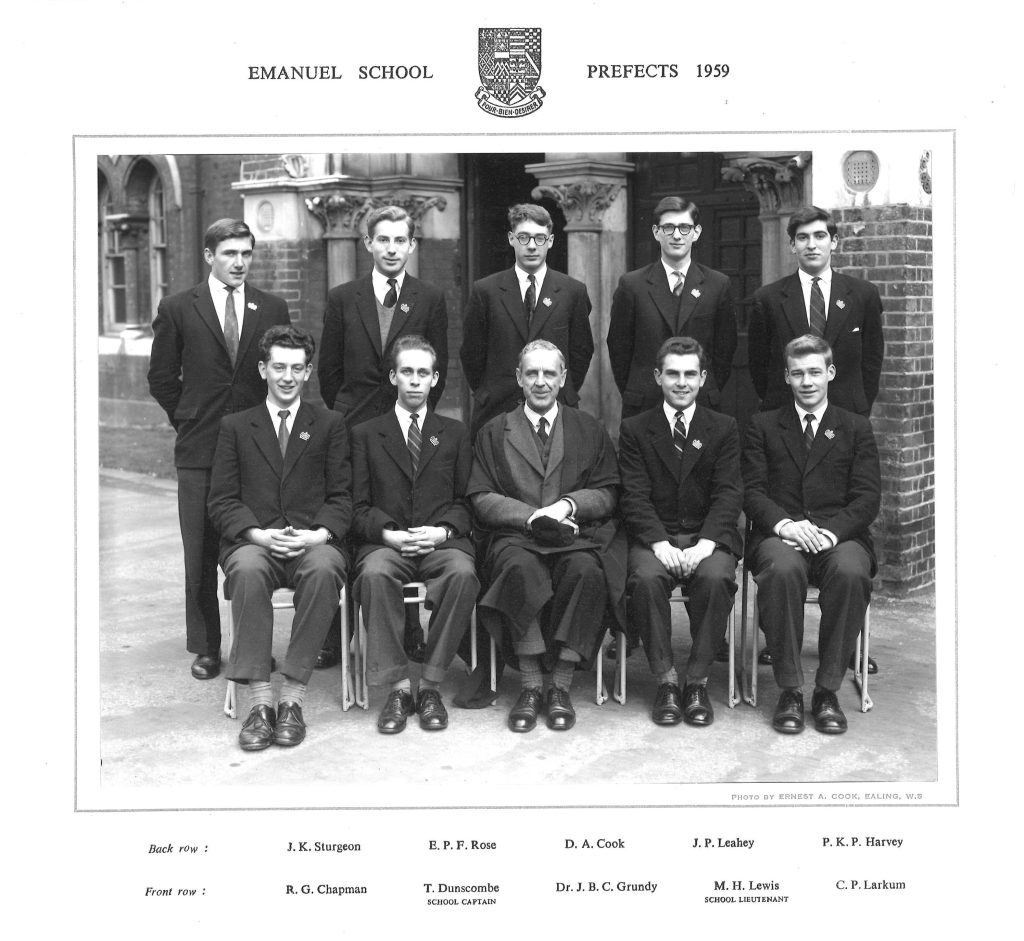

We love hearing of more than one generation of the same family attending Emanuel and were delighted to catch up with Dr Ted Rose when he returned to the school after more than six decades for an event involving his granddaughter. After leaving school in 1959, Ted studied Geology at the University of Oxford and went on to an incredibly rewarding and successful university career teaching and researching Geology and Palaeontology. He was also a military geologist for 21 years, making field studies during university vacation periods to support military projects, exercises or operations all over the world. On full retirement in 2003, Ted was appointed an Honorary Research Fellow at Royal Holloway.

We are very grateful to Ted for answering our many questions so thoroughly, with vivid recollection of how Emanuel School was in the fifties, his route through education and university and how to balance a full and satisfying life!

How did it feel to be back at Emanuel after 63 years away?

Amazing. In some ways, the school was so very different. Access by bridge across the railway line was new to me: in my day, the only access was from the road bridge, past the sergeant’s cottage, and down the long drive. There was then no security: no gate, and no reception desk inside the main entrance. What is now the school library was then the dining hall. So much else has changed, with many new buildings and major adaptations within the old buildings, that I simply don’t have the space to attempt to catalogue them all. All very impressive. And of course, even at the time I left, students and teaching staff in the school were still all male!

However, the school from outside the main entrance looked exactly the same as it did when I first arrived there, in 1952, and the headmaster’s study was still in the same place. It was there that my parents and I were interviewed for my potential admission to the school by the then headmaster, Cyril Broom, and later, in the science sixth form, I was taught German by his successor, Dr. Grundy.

My visit in December 2022 was to attend the Christingle service in the school chapel. The stairs up to the chapel were relatively new (and clearly fireproof!), but the chapel itself was almost as I remember. (I left the school after just one term in the Senior Sixth, in December 1959, after securing a place at St Edmund Hall in the University of Oxford for the following September.) Pews had been removed to create better access to the fire escape (I presume consequent on updated ‘Health and Safety’ regulations), and there were some new memorials on the chapel wall as well as overhead projection facilities, but much of the chapel was otherwise unchanged. I still felt a sense of continuity and belonging. Outside, it was good to see that the Hampden Hall was still standing, and the adjacent ‘gym’ – although the ‘gym’ was now a dining hall and much extended!

I gather you made a number of lifelong friends during your time at Emanuel.

For brevity, I’ll mention but two of them: Ian Wilson and Nicholas Hughes.

Ian and I became friends in the first year, when we were both members of form ‘1 ex’ – the ‘express’ stream for those deemed to have particular academic potential (followed by 1a, 1b and 1c). After forms ‘2 ex’ and ‘3 ex’, we had to follow the 4th and 5th year teaching that led to General Certificate ‘O’ levels and there our academic paths parted. I followed the science stream whereas Ian followed the arts stream. However, we retained our friendship throughout and then subsequently at Oxford – where Ian read history at Magdalen College, but we shared ‘digs’ in our second and third years as undergraduates. By curious coincidence, the day of the December 2022 Christingle service was Ian’s 55th wedding anniversary – I had been ‘best man’ when he married Judith! They now live in Australia, but we’re still in very regular communication. He has become very distinguished as an author of ‘factual’ books – but still has happy memories of being a library prefect and House Captain of Howe.

Nick Hughes was slightly younger but a member of my own house, Drake, who served as my best man when I married Claire in 1970. The Christingle service in 2022 was her first visit to the school! Nick went into banking for a career and was head of his bank’s office in Paris many years ago when I needed to visit Paris to study some fossil specimens in museum and university collections. I duly phoned his office to let him know I’d arrived in the city but the phone was answered by someone else: “I’m afraid Nick Hughes is not in the office at the moment, but I’m his boss, the head of European operations at the London office, here for an inspection: can I help you?”. Not wanting to give his boss the impression that Nick was misusing office time for personal matters, I quickly replied: “No thanks. Please just tell Nick that Ted Rose phoned.” “Ted!” came the response, “This is Ernie Cannings. How are you?” Ernie (who now prefers to be known after his second Christian name, as ‘Jim’) was a year ahead of Ian Wilson and myself at Emanuel. He too had gone up to Oxford, to read history at Magdalen. Nick Hughes went on to an increasingly distinguished career in banking. The son of an Old Emanuel, he and his wife brought up their family near-contemporaneously a few miles from the home that Claire and I developed for 30 years near Amersham in Buckinghamshire.

Moreover, years later Claire’s niece – daughter of her eldest sister – was to marry Roy Addison, who was only in Lower 5 Arts when I left the school, so I never really knew him then. But we became friends as well as family members in the years after his wedding, until he sadly died from pancreatic cancer in 2010. He had developed an impressive career in the TV industry, as documented in an obituary in ‘The Guardian’ newspaper: “one of the most popular and respected heads of press in the old ITV system.” ‘Flannels Day,’ the annual gathering of ‘old boys’ at the school that prospered in our days as students, had seemingly been abolished by the time we planned to attend it together.

You have mentioned that long-serving Geography Master Lt-Col. Charles Hill, made a strong impression on you. Which other members of staff influenced or helped you with your studies?

I have happy memories of ‘Charlie’ Hill – although I chose history rather than geography as an option for my ‘O’ level course, and transferred from the Army to the Royal Air Force section of the Combined Cadet Force as soon as I had passed the ‘Certificate A Part 1’ examination and was therefore allowed to do so. Although he certainly made a strong impression on me through personality, he did not influence my studies to significant effect.

Harry Hirst as senior chemistry master was probably the man of greatest influence, followed by Aaron Rogers as senior mathematics master because of his inspiring personality rather than my proficiency in mathematics. Kenneth Ulyatt, who taught my third ‘A’ level subject, physics, was clearly talented, but somewhat eccentric …

Curiously, the master who most influenced my later life never taught me: Mr. Paul (often known as ‘Joe’) Craddock, who taught German to students in the arts stream. If I remember correctly, his sister was married to Dr. ‘Jack’ Auden, Director of the Geological Survey of India and brother of the famous poet W.H. Auden. Mr. Craddock arranged that ‘Jack’ Auden should give a lecture to the school’s Science Society during a visit to England. I attended and was duly introduced to the great man after the lecture, for some advice. I had it in mind to apply to Cambridge for an undergraduate degree, but was unsure whether to read chemistry (my best and favourite ‘A level’ subject) or geology (a subject in which I had great amateur interest, but which I had not then been taught, and for which the school had no graduate on the teaching staff). ‘Jack’ Auden assured me that geology would be a good choice, but (although a Cambridge graduate himself) recommended that I apply to Oxford: on the grounds that it would provide me with a broader and deeper education in geology overall, and so improve my potential career prospects with employers such as national Geological Surveys. Cambridge at that time expected students to take three subjects (typically chemistry, physics and geology) for ‘Part I’ of the degree course, so students spent only a third of their time on geology, and for ‘Part II’ they had to choose between ‘hard rock’ geology (taught in the Department of Petrology and Mineralogy) and ‘soft rock’ geology (palaeontology and stratigraphy, taught in a separate department) – and there was then little co-operation between the two departments. In contrast, Oxford at that time expected students to pass the ‘Preliminary Examination in Natural Science’ in two subjects in their first year, geology and ‘physics and chemistry’ – but students who had passed physics and chemistry as single subjects at ‘S level’ (scholarship level, above ‘A level’) at school, as I was expected to do, were allowed to claim exemption from the joint subject and so spend all their time studying geology. From that base it was possible to take a wider range of geological courses in the second and third years than was then possible at Cambridge, all within a single Department of Geology and Mineralogy. I took the advice – and have never regretted it!

I believe you had some connections with Germany and then with the then Headmaster Dr ‘Jack’ Grundy who also taught German? Did you read any of his books, such as Brush Up Your German by any chance? He also wrote a memoir years later.

My mother was German by birth, born in Berlin. She trained in Germany as a primary schoolteacher in a seminary run by a teaching/missionary order of the German Evangelical Church. The family could prove impeccable Christian ancestry, but not (in the 1930s) loyalty to the Nazi government regime! The seminary, through ‘missionary’ contacts outside Germany, helped my mother find educational employment in England, where she in time met and married my very English father. I was born in St. James’ Hospital, Battersea, in September 1940, whilst London was subject to intensive German aerial bombing (‘the Blitz’) and whilst England was expecting imminent German invasion (Operation Sealion). My parents thought it prudent to name me after my English rather than my German grandfather, and not try to teach me to speak German during or after the war!

In the sixth form, science students were then expected to focus studies on three ‘A level’ subjects, but to choose two ‘recreational’ subjects to study for two periods each week for general interest. I chose Latin (because I knew that I might need to pass this at ‘O level’ for Oxbridge entry) and German (because this was deemed to be useful for all scientists). The small German class was taught by the headmaster to keep him in touch with the reality of teaching in addition to the administrative duties that otherwise filled most of his time. I quickly realized that two periods a week of ‘recreational’ Latin would not get me a pass at ‘O level,’ for which four exam-orientated periods a week were normally required in the 4th/5th year arts stream. I needed to give up German without upsetting the headmaster: an upset that might not enhance my school career! Accordingly, after one year of German I spent the summer holiday in Berlin staying with a sister of my mother, who was married to a dentist. They spoke no English, so my German improved rapidly! Next term I asked a very surprised Dr. Grundy for permission to sit the exam for ‘O level’ German that term – after only four terms of two lessons per week rather than the normal six terms of four lessons per week standard for an ‘O level’ course. I passed, to his amazement (with grade 3 when a grade 5 would have sufficed for a pass) and he therefore readily admitted that I had already achieved more than was expected for his course. I was allowed to give up German for private study of extra Latin and, with the polish provided by more Latin in my term in the senior sixth, I duly passed Latin at ‘O level’ – in January 1960, so technically the month after I had officially left the school. I was thus fully exempt from all subjects at ‘Responsions’: the examination that permitted matriculation at Oxford.

What are your fondest memories of school?

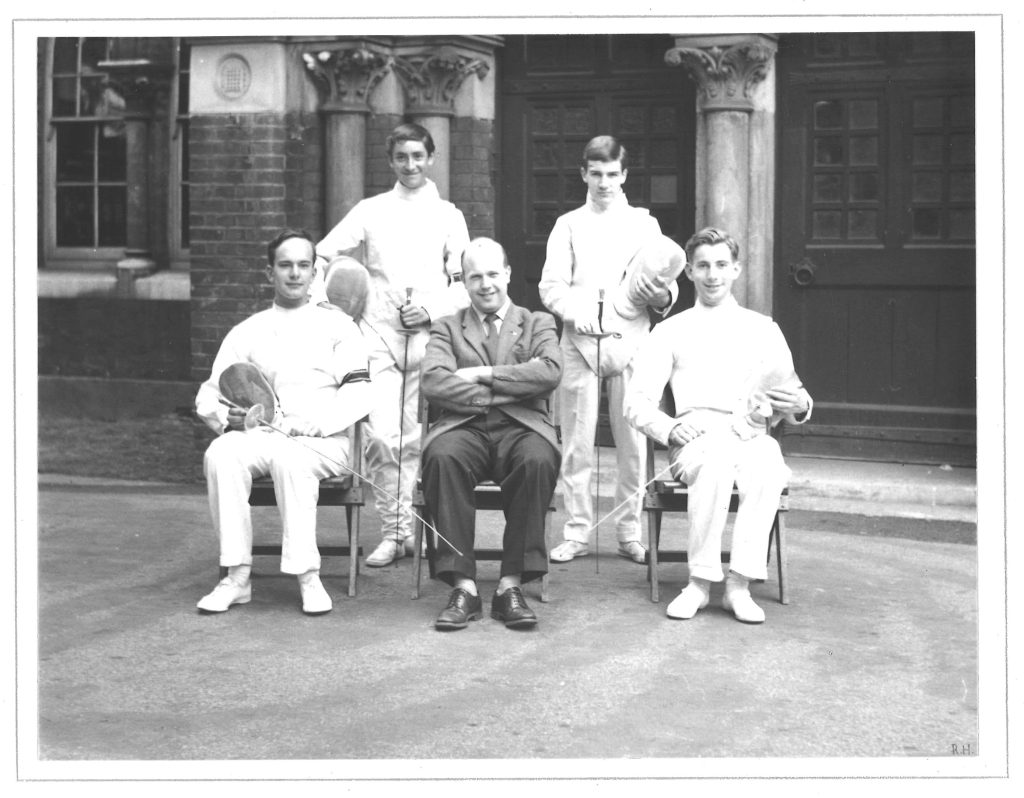

Too difficult to answer: I enjoyed all my class teaching, the opportunities to join extracurricular societies (notably the Natural History Society), the fencing club, and the Combined Cadet Force (the CCF). My worst subject was probably woodwork (although I did not dislike this, and in later life came to wish that I had become more proficient at it). And I was by no means the world’s greatest rugby player, although I did try to do my bit for my house when required – not to great effect …

How did you benefit most from the CCF? That and the earlier OTC were amongst the most popular and highly attended school activities of the twentieth century.

I joined the CCF in September 1954, at the age of 14 and so when expected to do so. I was encouraged by the school ethos (all those memorials in the school chapel, the masters who had nearly all either served in the forces during wartime or during National Service – the period of conscription afterwards – and the ebullient and ever-present Lieutenant Colonel ‘Charlie’ Hill) and by my parents who, with memories of the Nazi threat fresh in mind, thought it a clear public duty to prepare to defend the British democratic way of life. With the prospect of National Service before me after leaving school, I decided that doing well in the CCF might improve my chances of gaining a commission and an interesting appointment when that Service came – and found to my surprise that I was awarded the CCF’s annual recruits’ prize and Warren Cup at the end of the academic year.

I was not particularly stimulated by what I was taught in the Army section of the CCF, so transferred as soon as I was allowed to do so to the RAF section – which had its own training hut in the school grounds, and which had a much more exciting training day each term (based on RAF stations) and more exciting week-long ‘camps’ (comfortably indoors!) at RAF stations during the Easter and summer holidays. These all taught me technical skills that I found interesting (including elementary meteorology, map reading and cross-county orienteering) and allowed me to visit RAF stations and so the surrounding areas in many parts of England and Scotland. In time I became the Flight Sergeant leading the section.

Just before I left school National Service was abolished – but the CCF training I had received at school encouraged me to join the Officers’ Training Corps (the OTC) on admission to Oxford.

Is it true your name first appeared in a scientific paper when you were only fourteen years old? Little were you to know that you would later author over 200 academic papers over the following decades!

Yes, in the acknowledgements ending ‘Additions to the London Clay Fauna of Oxshott, Surrey’ published in 1955 in the journal The London Naturalist by two palaeontologists on the staff of London’s Natural History Museum – at that time known as the British Museum (Natural History).

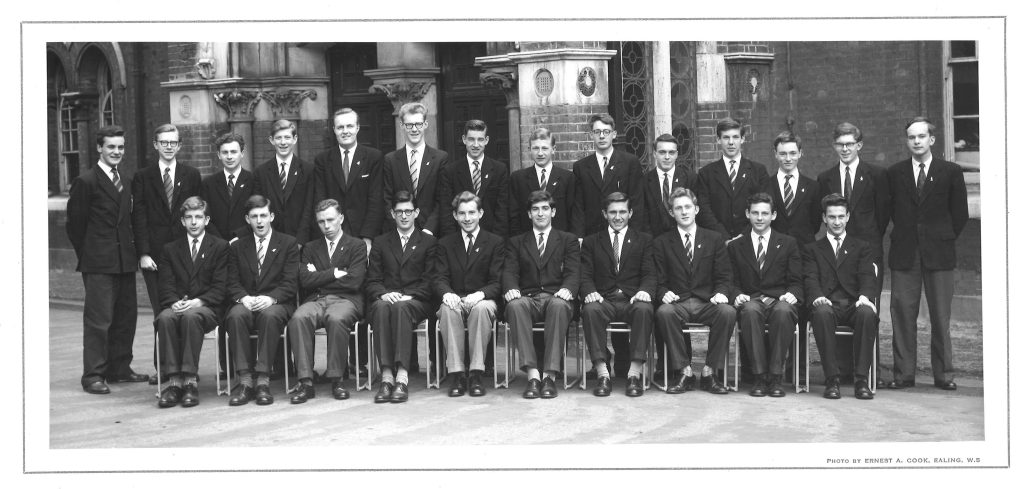

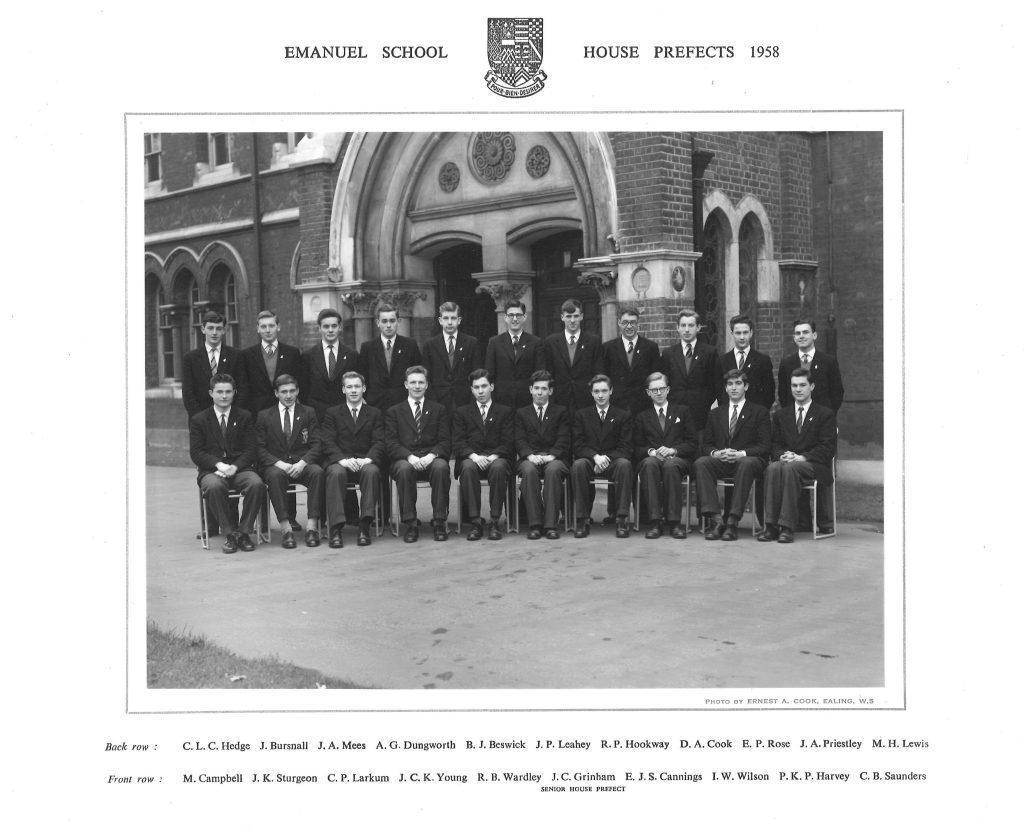

I developed a friendship in form 1ex with David Cook, which continued through the science stream until we both went up to Oxford at the same time, David to read chemistry at Oriel College and then to continue (as I did) for research leading to a ‘DPhil’: the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. (We were both prefects of the school at the same time and shared a study until I left – and he remained at school for the next two terms, becoming School Captain.) We shared an interest in fossils and used to bicycle together from our homes to visit quarries to search for them, mostly in Cretaceous Chalk, to the south and east of London – something no longer possible, for many reasons. Other boys from our year would join us, so peak visits involved about a dozen cyclists (one of them John Penn, who was to gain a BSc in geology at Kingston Polytecnic – as Kingston University then was – followed by a PhD and appointment to the teaching staff there as a lecturer). We took our fossils to the Natural History Museum for identification – and after several such visits, the staff stopped identifying the fossils for us and taught us how to use books in the Museum’s library to do this for ourselves. (The present system at the Museum is very different.) David soon became distracted by rowing (he eventually became Captain of Boats), but two members of the Museum staff persuaded me that my time would be better spent looking at fossils from the London Clay rather than the Chalk. I did so; over about a year I presented four sets of specimens (on request) to the national collection held by the Museum, for each of which I received an official letter of thanks from the Museum Director, Sir Gavin de Beer; and saw my name appear in print. But thereafter I needed to focus on ‘O level’ studies rather than fossil collecting!

When I came much later to write academic articles myself, they were to be on fossil sea urchins (the sort of fossils I had been finding in the Chalk), limestones of the Mediterranean region (especially of Malta and Gibraltar), and on the history of military applications of geology.

You obviously had a very successful career at Emanuel, becoming both a Prefect and House Prefect of Drake, what other activities or sports did you get involved in or enjoy?

Looking at my school reports (yes: I have them all still!), I note that in the sixth form I was a member of the Science Society, the Dacre Society and the Christian Union. I had been a committee member of the Science Society and chairman of the Natural History Society in the Lower Sixth, interests carried on from the Fifth form when I was also a member of the Music Society and the Chess Club. It seems that my first documented ‘other activity’ was the Natural History Society, which I joined in the Second Year, followed by the Chess Club and the Combined Cadet Force in my Third Year. I am sure that the range of activities then available in the school was much narrower than it is at present, but I certainly enjoyed my choice of activities.

What inspired you to study Geology at Oxford? Was the school supportive of boys who wished to attend higher education?

Inspiration to study geology came from fossil collecting at localities within cycling distance of my home, i.e., within about a 40-mile radius from Emanuel, and to study at Oxford from advice given by Dr. ‘Jack’ Auden, as described above.

The school certainly supported boys who wished to attend higher education – or the officer training colleges of the army (Sandhurst), navy (Dartmouth) and Royal Air Force (Cranwell). At Oxford, there were then about a dozen Old Emanuel undergraduates in the university as a whole, spread over the three undergraduate years, and we formed our own Oxford Old Emanuel Association – with an annual dinner to which we invited two masters from the school, both ex-Oxford but one from the science/mathematics stream and the other from the arts: initially mathematician Aaron Rogers and historian Dennis Witcombe.

You held various lecturing positions and taught both Geology and Paleontology. Was this your dream job and something you always wanted to do?

As my three years as a research student at Oxford came to an end, I realised that I enjoyed both research and being in a university environment – so I applied for the three ‘assistant lecturer’ jobs then being advertised and was called for interview for all of them. The first interview was at the University of Edinburgh, where the staff had to explain that although university regulations required the job to be advertised openly, it had been created to provide a potentially permanent position for a post-doctoral research student ending his temporary contract in the university – and the details of the job description had been drafted so that only he could possibly meet them all. I did not get the job – but made some friends for life. The next interview was at Bedford College in the University of London, at that time located within Regent’s Park and so within easy commuting distance from my parental home. I was offered that job immediately after interview and promptly accepted it.

It became my dream job but began as a nightmare! I submitted my doctoral thesis to the registry at Oxford just before the deadline of 5.00 p.m. on the last Friday in September 1966 (so precisely within the three-year period ideal for completion), moved from Oxford to London over the weekend, and reported for duty at Bedford College on the Monday morning – to be told that although I would only be paid as an Assistant Lecturer I was expected to fill the teaching load and many of the administrative duties of the Senior Lecturer who had just left (to become Professor and Head of the Geology Department at Trinity College Dublin). On 1 October, the university had brought in a new modular degree structure which meant that each college in the federal University of London College was now to teach all the courses required for the London degrees internally, rather than send them to different colleges for different courses to benefit from the wide expertise thus available. Bedford College had the smallest teaching staff of the seven London geology departments at that time, so its staff had to share a particularly heavy teaching burden, and as the Deputy Head of Department my Senior Lecturer predecessor had agreed to teach a large number of courses – which existed by a name and number only: nothing else. (Teaching slides for the ‘old’ courses he had taken with him to Dublin.) Moreover, Bedford College had been founded ‘for Women’ over 100 years previously but agreed to accept men as undergraduates some months before I arrived. This was not expected to affect other departments significantly in the short term but predicted to increase the number of students for single-honours geology – at that time viewed as an almost exclusively masculine subject (from an average of 4 to 24 students admitted annually, as events were to prove). Starting on the Monday with a blank sheet of paper and no slides to illustrate any lectures, I had to prepare the outline syllabus for the first of several courses in a three-year degree programme, write my first lecture and prepare its following two-hour practical class ready to deliver on the Thursday of that week. Similar weeks followed over the next three years until all my courses in the degree programme had been created and presented. Then the nightmare became more of a dream … But I confess that I found rising to the challenge and coping with a level of responsibility that would be unthinkable in the present world for someone so young to be exciting.

Preparing for my very first lecture and practical class, I noticed an unusual name on the student registration list: John Bursnall. Checking his admission form, I proved that this was indeed my predecessor as Head of Drake House at Emanuel! (He had not settled into a career on leaving school and decided to become a geology student much later than normal.) I decided that it would be appropriate to wear, when I delivered the lecture, the Drake House Colours tie that as House Captain he had formally presented to me at a House meeting about eight years earlier. At the end of my lecture, I dashed quickly into the adjacent laboratory whilst the students gathered their pens and papers and gently eased themselves out of their seats to follow me. In the laboratory, I saw John already seated. “What are you doing here?” he exclaimed in surprise. “I’ve just joined the department” I replied. Assuming that meant I had joined as a research student and would be assisting teaching in the practical class, as then usual for research students, he decided: “We must talk later. There is a new lecturer who is a whizz kid from Oxford, but I’ve just missed his lecture because of a change in schedule. I need to give a good impression when he comes in, so be seen to be working on the specimens rather than chatting.” I assured him “Don’t worry. I’m the whizz kid from Oxford …” Despite this inauspicious start, John went on to complete his three-year degree very successfully!

Could you tell us a little bit about your 21 years as a military geologist?

I gained a commission in the reserve army, at that time known as the Territorial Army, through the Officers Training Corps at Oxford. That carried an obligation to continue to serve in the TA after graduation. The TA suffered two major reorganizations in the early years of my service and after over three years in the artillery, followed by two in the infantry, I applied in 1969 for transfer to the Royal Engineers, potentially to serve as a military geologist. About six weeks after passing an interview board chaired by a brigadier, I found myself on a Royal Air Force flight to the then Headquarters Far East Land Forces in Singapore, via refueling stops in the Middle East and the island of Gan in the Indian Ocean. In Singapore I was issued with tropical uniform and joined a regular army reconnaissance team flown to Thailand to determine the best areas in which to deploy a well drilling team from the Royal Engineers, tasked to provide military aid to the civilian community by enhancing supplies of drinking water. My role was essentially to make a reconnaissance geological map of an area comprising some 2,000 square miles of mountain and jungle in about two weeks – something not easily done at that time without military logistical support! My area included the famous ‘bridge over the River Kwai’ – and proved so interesting that I remained a military geologist for the following 21 years, making field studies during university vacation periods to support military projects, exercises or operations in many parts of the world, including Germany, Gibraltar, Malta and Cyprus in Europe, Thailand and Hong Kong in the Far East, and Belize in Central America. Many of these studies were to enhance water supplies by drilling wells in the best rocks and locations. British regular armed forces have no geologists who serve as such, so rely entirely on a small group of reserve officers to provide appropriate geotechnical expertise. I led the group for 16 years.

When you retired from lecturing, did you remain busy with your geological interests?

On full retirement in 2003, I was appointed an Honorary Research Fellow at Royal Holloway. This enabled me to continue as a university examiner and committee member when appropriate, to help edit and mostly write four books, and to write over 100 journal articles or book chapters on historical aspects of military geology: activities that no longer required a laboratory or research funding. I continued to attend and present papers at conferences both in the UK and overseas, and to participate in the activities of the Geological Society of London and other academic organizations.

What advice would you give to students interested in pursuing a career in Geology at university in 2023? What opportunities might lie ahead?

If you have real enthusiasm for the subject, go for it! Career opportunities are always changing, so young people today need to be prepared for that. For example, there are fewer posts available in universities and museums for palaeontologists specializing in invertebrate fossils than in my student days, and scope for employment as an exploration geologist in the coal mining or petroleum industries has declined dramatically. However, there are still opportunities in many fields: hydrogeology, engineering geology and environmental geology to name but a few. Also, there are amazing opportunities for research in universities and elsewhere, on topics both terrestrial and oceanographic, and even extra-terrestrial. The Geological Society of London, the UK’s national geological organization, has a website that provides extensive information on ‘Careers in Geology.’

What else have you enjoyed during retirement?

Spending time in and about my home in Dorset and with my wife of nearly 53 years – and trying to keep suitably involved with the activities of my two children and five grandchildren!

If you had the ability to give your teenage self some advice, what would it be?

Do something with your life that you really enjoy and to which making an effort is a real pleasure, but something which is useful to other people and that might also leave a lasting legacy.

Mr T Jones, Emanuel School Archivist

Edward Rose